By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

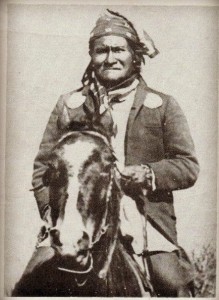

Geronimo and His Band in Captivity

About 4:30 o'clock Saturday afternoon a special train, consisting of three emigrant cars and a passenger coach, arrived in Algiers over the Southern Pacific railroad from San Antonio, Texas. The train contained a remarkable class of passengers and attracted great interest and curiosity. The passengers were a guard of forty infantrymen under command of two officers, and Geronimo, Natchez, and their tribe of Apache Indians, consisting of fifteen bucks, with seventeen squaws and children.

Geronimo and his men are destined for Fort Pickens, near Pensacola, Florida, and the women and children and two scouts for Fort Marion, at San Augustine, Florida. The names of the Indian braves are Geronimo, Natchez, Porcio, Fenn, Abnandria, Mahi, Yahenza, Fishnoith, Touze, Bishi, Chona, Lazalyah, Molzos, Nulthigal, Sophonne and Louah. The band, small though it was when captured, at one time numbered hundreds of Indians. They have been on the warpath for years and their numbers have gradually diminished. Some were killed, some captured, others died; and though their numbers dwindled down to but fifteen braves they were defiant, and had they possessed the ammunition, horses and food necessary, would have continued the fight to an indefinite time.

The band was captured on the 4th of September — or at least they surrendered on that date to Captain Henry W. Lawton, of the Fourth United States Cavalry. The capturing party consisted of Captain Lawton and Lieutenants Smith, Walsh and Brown, of the Fourth Cavalry, Sergeant Wood and First Sergeant C. O. Taylor, Sergeant A. Cabiness, Sergeant A. H. Schenck, Sergeant T.Ryan, Corporal W. J. Lynch, Corporal F. McKenna, Farrier F. Lawrie, Sadler J. V; Spangler, Wagoner J. M. Smith, Privates H. Conway, L. C. Crispin, J. Duffy, W. C. Flagg, C.Hinsel, J. Huber, M. J. Jennings, F. Lanna, J. Lynch, A. Lapant, E. T. McNally, F. Mehan, C. Rioport, J. Rowland, F. Smith, J. Simon, L. Vinton, and G. Williams of the Fourth Cavalry.

This command started in pursuit of Geronimo and Natchez and their tribe in the early part of the past summer. At the time the impression prevailed that Geronimo would proceed to his stronghold in the Sierra Madre Mountains, and it was planned to attack him there. When the Fourth Cavalry took up his trail, however, it was found that the Indians had divided up into small bands which committed great depredations in various sections of Arizona and Sonora, and the original plans of the troops were abandoned.

The Fourth Cavalry kept the trail of the hostile Indians and followed it into the Azul Mountains in Sonora, having marched up to the latter part of last June, a distance of 1,396 miles over the roughest, most desolate part of the American continent. The Indians were frequently encountered and once were surprised. In the latter part of June the trail of the Indians was lost and no trace of them could be found. The pursuing troops were reinforced by fresh men and thirty Indian scouts from the Unas and Majoras tribes.

A supply camp was established in Sonora, and on the 17th of July the command, refreshed by rest, left the camp on foot and took up the trail of the Apaches, which led to the Yaqui river. The weather was intensely warm and some of the men fainted from heat and fatigue, fully two-thirds having succumbed. It was evident, however, that the troops were gaining on the Indians, for the trail became larger, the original band being strengthened by accessions from smaller bands, forming one large company. The scouts were advanced and the signs became fresher each day. On the 14th day of July the Indian camp was located and an attack was at once determined upon.

The camp was captured, but the Indians escaped into the mountains, having taken alarm at the appearance of the scouts, whom they had detected before the troops could come up. Geronimo, Natchez and their followers, fourteen braves and seventeen squaws and children, crossed the Yaqui river and went northwest. The troops encountered great difficulty in following them, owing to swollen streams and heavy rains which obliterated the trail.

The Apaches then moved towards the north, murdering men, women and children, and burning houses and stealing stock. They took refuge in the mountains near Frontreras, Mexico, and then sued for peace. Lieutenant Gatewood, of the Sixth Cavalry, and two Indian scouts entered their camp and found that the Mexican authorities had already opened communications with them, and the Mexicans objected to the interference of the Americans. It was agreed that the Americans, pending negotiations with the Mexicans, should take no steps for forty-eight hours. On the 25th of July, Geronimo and several of his men came into the camp of the Fourth Cavalry, and promised to bring the remainder of his band down from the mountains, which he did. The surrender, however, was not formally made until the 5th of September, and on the 8th of the same month the Indians, under guard of the Fourth Cavalry, left Fort Bowie, Arizona, for San Antonio, Texas.

On September 10 the party arrived in San Antonio in charge of Captain Lawton. The Indians remained in San Antonio until Friday last, when they were placed on the special train which arrived last evening.

General Miles' order announcing to his troops the close of the Indian campaign was received a few days ago. He congratulated them on the establishment of permanent peace and security against further depredations of the Apaches. General Miles mentioned individual acts of heroism on the part of officers and men during the campaign, the most conspicuous of which was the conduct of Lieutenant P. H. Clark, Tenth Cavalry, and Private John Conrad of Captain Hatfield's Fourth Cavalry troop. General Miles, continuing his order, says no hesitation is felt in pronouncing this steady, tireless march of resolute men in their purpose to succeed as one ofthe most remarkable in the history of military achievements. The march of the troops, thirty miles in two hours; Benson's ride of General Miles in nineteen hours, and Dr. Woods' skill and remarkable marches with detachments of infantry are worthy of mention. The discomfiture of the Indians had been such that in June evidences of weakening had been discovered, and a most vigorous campaign of three months, in which they had been pursued more than two thousand miles. An opportunity occurred for Lieut. Wilder, Fourth Cavalry, then with a command near Frontreras, Mexico, to notify them to surrender. Four days later Lieut. Wood, Sixth Cavalry, rode into their presence at the risk of his life, and, without the assurance of a peaceable settlement, demanded their surrender through two friendly Apaches. Finding no place of refuge and troops in every section, the leaders desired to see Captain Lawton and requested favorable terms. Their requests were refused and Captain Lawton was authorized to receive their surrender as prisoners of war.

The Indians agreed to surrender to the department commander and marched eleven days parallel with Captain Lawton's command to Skeleton Canyon, Arizona, for that purpose, and on the 4th of September, on learning that their tribe was being moved from their native country, worn out and exhausted, with not enough ammunition to make another fight, with the expectation of banishment for life, they surrendered as prisoners of war, trusting entirely to the honor of the brave officers and soldiers who had pursued and fought them incessantly for four long, weary months, and placed themselves and their families at the mercy of the government.

For some the War Department was undecided what action to take in regard to the captives. Owing to the numerous murders and depredations committed by them the people in the Southwestern States demanded their execution. At length it was determined to imprison them far away from the scenes of their crimes and to separate them from their families. The women and children were ordered to Fort Marion and the men to Fort Pickens, Florida.

At 4 o'clock last Thursday evening a train consisting of four cars— three emigrant cars and one passenger coach — left San Antonio with the captives. In the first coach were the women and children, in the second a guard of forty men, consisting of the entire Company K and a detachment from Company B of the Sixteenth United States Infantry; in the third car were Geronimo, Natchez, Chaha, Geronimo's son; Percio, Geronimo's brother; Fenn Abuadwa, Nahi Yakusha, Fishnolto. Touze Bishl, Lazapah Mozo, Kilthdigai, Sephonne and Lehahah, and in the fourth Lieut. H. Woodbury, commanding the detachment; Lieut. E. Chandler, Lieut. J. T. Anderson, Lieut. C. C. Balton, all of the Sixteenth Infantry, and Surgeon F. J. Ives.

The prisoners were at first considerably frightened as to their fate, believing that they were to be killed; but when they were informed of their destination they became apparently contented; although it meant separation from their wives and children. Nothing worthy of mention occurred during the trip, and efforts were made to keep the arrival of the Indians a secret. The matter, however, leaked out, and when the train reached the Algiers depot of the Morgan Railroad there was a large crowd of men, women and children on hand to see the famous Indian chiefs and their band.

The bridges on the incline in Algiers were lined with people and many boarded the transfer boat in hopes of obtaining a long and good look at the Indians.

Geronimo had a seat at the end of the car nearest the engine, and while the car was going down the incline he peered through the window, the sash of which was down, at the many faces and the novelty of everything around and about him. Natchez was seated in the middle of the car, and was also busily engaged in taking in the sights through the window. When the train was safely on board the transfer boat Division Superintendent Owen, of the Southern Pacific Railroad, boarded the train with a party of three or four, including a reporter of Picayune. Under the leadership of Lieut. Woodbury, in command, they entered the car in which the Indians were. Nearly all of them had hats on their heads — felt hats, except Genorimo, who had on a common straw hat. They were indeed a dirty and sorry looking set of men. Squalor and filth were apparent on their scant apparel and persons. The majority of them sat or declined in their seats without nether garments, and eyed the party which entered with indifference.

Geronimo, Indian though he was, must have detected the presence of a reporter, for he hid himself in the closet. Lieut. Woodbury went to that side of the car, and through Mr. George Rattan of New Mexico, the interpreter, informed Geronimo that his presence was desired and that he was wanted to say something. The medicine man of the Apaches sent back word that he did not want to be interviewed. One reporter, thinking to induce Geronimo to speak, sent word that "his paper was ready to give his side of the story." It wouldn't take however, and Geronimo remained inaccessible.

While the boat was making its way across the river, the Indians, whose view was shut out by the sides of the transfer boat, retained their seats in the car. On reaching this side a crowd of fully 1,000 people were congregated along the tracks leading to the incline. An engine was coupled to the car and the train was pulled out and alongside of the Louisville & Nashville train of four coaches, which stood on a side track. The Indians had only a glimpse of the broad river between the end of the incline and the train to which they were to be transferred, but it was sufficient to arouse their wonder and curiosity. The guards had great difficulty in keeping back the crowds on both sides and between the two trains.

After some time everything being in readiness the order was given to change cars. The Indians, clumsy though they appeared in their movements, were lithe and active in jumping from car to car. They had all donned their trousers or leggins for the time being, and stepped forth from one car into the other without displaying any concern. Natchez the great war chief of the Apaches, was the third to step out. Geronimo got out at the end of the train, near which he had been seated, while all the others disembarked from the other end.

The cushions in the coach to which they were assigned, as well as the changeable back seats, attracted their attention and appeared to afford them satisfaction and delight. Geronimo seated himself at a window in the middle and on the east side of the car, where he could see the river and the vessels lying at the wharves. Natchez also amused himself thus, as well as several others of the band. Geronimo at once relieved himself of his nether garments, doubtless for the sake of comfort.

Geronimo is 65 years of age and has a wrinkled face. His eyes, however, are bright and his hair long, straight, and glossy black. He wore white cotton trousers, a straw hat, cotton shirt, and had on a vest. He is the big medicine man and prophet of his tribe and is looked up to with awe and respect even by the chiefs. Natchez is a fine specimen of physical manhood, standing 6 feet 3 inches in his moccasins and straight as a young pine. He is symmetrically built, and agility and activity are evident from his quicksteps. He is the son of the late Cochise, the first war chief of the Apaches. Natchez is the hereditary war chief of the Apaches, and, judging from the fealty of his followers, must have suited them exactly. He wore boots, a white shirt, white trousers tucked in his boot tops, and a vest. None of the savages were handsome, but Natchez was the best looking one among them. The remainder of the band all looked alike — large broad faces, aquiline noses, and long black hair flowing down their backs. A few of them were bare-headed, a piece of red cotton or ribbon being used to keep their hair out of their faces.

The squaws and children were transferred to the rear car of the train with their packs, and then the soldiers changed cars.

Among the many persons who were on the Levee to see the Apaches arrive were two Choctaw Indian squaws, who stood looking at their warlike brethren without betraying any feeling. They were vendors in the French Market and civilized. Many comments were made by the people gathered there to regard the Indians, but the most common were words of surprise that a small party of ragged and naked men such as the prisoners could carry on war with troops as well armed and disciplined as were the United States soldiers. Dr. Ives, when such a remark to that effect was made in his presence, stated that if those who made the remark could see the country in which the Indian war was carried on they would cease to wonder. It is a country of natural fortresses, and as long as food and ammunition lasted the handful of Indians there could defy an army. The country in which the Indians operated is one replete with game of all kinds, especially deer and antelope, while the mountains afforded strongholds from which it was impossible to dislodge them. At 7 o'clock last evening the special train on the Louisville & Nashville Railroad left the city for Pensacola, Florida. Thence Geronimo, Natchez and the braves will be transported to Fort Pickens, at the eastern end of Santa Rosa Island, at the entrance of Pensacola Harbor. The women and children will be sent to Fort Marion, at San Augustine, where they will be lodged with the Warm Springs Indians and others who had been friendly to the warlike Apaches. Fort Pickens is one of the few fortresses which were not captured by the Confederate forces during the war. It is a large bastioned and case-mated fort and was named after General Pickens of Revolutionary fame. Fort Marion, Florida, is the oldest fort in the United States.

(Editor's Note.—The newspaper from which the above article was copied, was printed October 28, 1886, 65 years ago. Geronimo was kept at Fort Pickens for a time, and was later sent to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where he spent the remainder of his days, and died there in 1909, at the age of about 90 years.)

*************

20,000+ pages of Texas history/genealogy on a searchable flash drive. Get yours today here.

‹ Back