By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

The Trail of Blood Along the Texas Border

The Trail of Blood Along the Texas Border

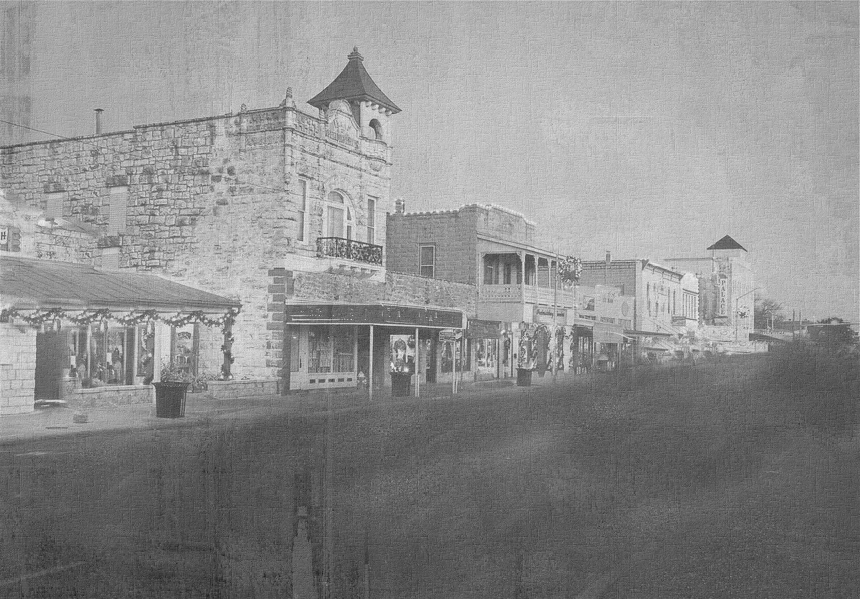

Fredericksburg

Fredericksburg

This series of Frontier Stories was written several years ago by John Warren Hunter, now deceased. One article of the series will appear each month in Frontier Times.

In early 1855, Mathew Taylor and Joe McDonald, each with large families, left Illinois and settled on Spring Creek, fifteen miles west of Fredericksburg in Gillespie County. At that time, Fredericksburg was the chief seat of the Prince Solms Colony of Germans and was merely a village of pole cabins. The settlement formed by McDonald and Taylor was on the extreme border. The government maintained a small garrison of regulars at Fort Martin Scott, two miles below Fredericksburg, also at Ft. Mason, and later in the year, in 1855, Fort McKavett was established. The McDonald and Taylor families engaged in stockraising and farming, the latter to a limited extent wherever the waters of Spring Creek could be utilized for irrigation.

These men were devoutly religious, and after completing their little log cabins, they erected a family altar, installed the Bible as their guide, and taught their children to worship God and obey His divine precepts. Nature was generous to these pioneers. Game was plentiful, wild bees abounded in trees and caves, and life would have been a long, joyous round of rural pleasures if not for the continued menace of the savage Indians whose path intersected their settlement. Mr. Taylor recalled that the hunting grounds in those days encompassed the Upper Llanos, the Conchos, and the Guadalupe regions. During the buffalo season, he and his sons, along with the McDonald boys, paid their annual visit to the Conchos, established their camp near the spring at the confluence of the two main streams, where San Angelo now stands. They would remain there until the buffalo had left or had been driven away, and then return home laden with dried meats sufficient for the year's supply.

Mr. Taylor also mentioned that he and his brother-in-law, Joe McDonald, were the first to raise a crop of corn in Kimble County. They chose a spot in the forks of the Llano, in the river bottom, near where Junction City stands today. Using a rudimentary "bull-tongue" plow, they prepared the ground (about two or three acres), planted the corn, and returned to their homes on Spring Creek, which was thirty miles away. Later, they came back to plow and tend to their crop. When the corn reached the roasting ear stage, bears came to claim their share of the harvest, but enough was left to reward the pioneers for their labor.

Shortly after the arrival of the Taylor and McDonald families, the Nixon and Joy families moved from Arkansas. The Nixons settled on Squaw Creek, and the Joys settled on Beaver Creek. These two settlements were roughly ten and sixteen miles from the Taylor settlement on Spring Creek. In those days, despite the distances, everyone considered each other as close neighbors, bound by a common sense of danger that forged deep bonds.

Just before the outbreak of the Civil War, Monroe McDonald married Miss Beckie Taylor, the daughter of Matthew Taylor. Around the same time, Lafe McDonald married Miss Alwilda Joy, the sister of Tobe Joy, who later gained renown as an Indian fighter.

To the old frontiersmen, it was a well-known fact that an Indian never forgets or overlooks a locality or settlement where one of his tribesmen has been slain. Revenge was almost certain to be exacted upon the dwellers of that particular area.

The settlers in Gillespie County were not seriously molested by the Indians until the beginning of the Civil War when U.S. troops were withdrawn from the frontier. Up until that point, the Indians were somewhat friendly, occasionally visiting the settlements, trading with the people, and sometimes leaving with unpaid horses.

The first in a series of troubles with these pioneers began in 1862 when an Indian approached Monroe McDonald's cabin, begging for food. Monroe supplied him and took him to his father, Joe McDonald, where he was kept under guard for a few days before being handed over to the sheriff of Gillespie County, who placed him in jail. What became of the Indian is uncertain, but rumors circulated that a cruel and swift vengeance was meted out to him.

In early February 1863, Captain John Banta and ten others, including the McDonald brothers, were scouting along Johnson's Fork of the Llano River. It was a cold day with a light mist in the air. They stumbled upon an Indian trail heading towards the Spring Creek settlement, and their intuitive knowledge of the frontier soon revealed that there were eleven Indians in the group, all on foot. They cautiously followed the trail until they reached a ridge overlooking the head draw of the Pedernales River, where they suddenly encountered the Indians. The Indians had not anticipated danger and had halted on a hillside, busy with their weapons, which were in poor condition due to the wet grass and long travel.

The Texans charged the Indians, who fled and tried to reach a group of live oaks in the valley below. As the Indians scattered, a running battle ensued. Each Texan engaged with his Indians, and when cornered, the Indians would turn and attempt to use their bows and arrows. However, the rain had dampened their bowstrings, making them ineffective. The Texans, armed with Colt's pistols, faced their own challenges, as the government-issued ammunition was of poor quality, especially the percussion caps, which were not waterproof. When placed on the tubes, the first shot would often jar the remaining five caps loose, causing them to fall off.

Despite these challenges, the battle intensified, and the Indians eventually rallied around their leader with defiant yells. The wounded Texans continued to charge until six Indians had fallen, including their chief. The remaining five Indians escaped into the brush and were pursued for some distance but ultimately got away.

During the last charge, a shot from Captain Banta's pistol had broken the old chief's back. While pursuing the fleeing Indians, the wounded chief managed to drag himself to a nearby live oak. When the pursuers returned, they found him reclining against the tree's roots. As they approached, he began to chant his death song, a strange and eerie melody that held their attention until he finished. The chief clutched a long knife and, summoning all his remaining strength, thrust it into his own heart before falling lifeless to the ground.

The Texans collected six scalps, six bows, six quivers of arrows, and a few worthless Indian articles as the spoils of their victory. While these trophies marked the end of six Indian lives, they also signified the end of Indian raids on their settlement, and the Texans returned home without suffering any losses.

Sometime after this event, around 1864, the Taylor and McDonald ranch was established on the Pedernales River near present-day Harper, about ten miles from Spring Creek. It appears that after his marriage, Monroe McDonald lived with or near his father-in-law, Mr. Joy, in Threadgill, which was several miles from the Taylor ranch.

During these challenging days, clothing for these pioneers was either homemade or traded, sometimes both. Spinning wheels, weaving blades, and warping bars were essential tools in every frontier household.

A few months after Captain Banta's encounter with the Indians near the Taylor ranch, another tragic incident occurred. Mrs. Lafe McDonald and her mother, Mrs. Joy, left the Joy ranch in a buggy, headed to the Taylor ranch with a load of thread they had spun. The thread was meant to be woven into cloth by Mrs. Taylor. However, a few miles into their journey, they were surrounded by a band of Indians and killed.

This raid appeared to be motivated purely by revenge. The Indians did not take the horse pulling the buggy or any items from it. The family only learned of the terrible tragedy when, a couple of hours after the two ladies left the ranch, the horse returned to the ranch gate, still harnessed to the buggy. When the family investigated, they discovered both women dead in the buggy. Mrs. McDonald's head had been severed and was found under the buggy seat, while Mrs. Joy's throat had been cut from ear to ear.

John Joy Sr., the husband and father, swore eternal vengeance against the Comanches upon viewing the remains of his wife and daughter. He was relatively well-off, owning a substantial stock of cattle, horses, and hogs, along with a good supply of money. He gathered his sons and declared his intent to dedicate them to the task of killing Indians. He placed them in charge of all the family's ranching interests, reserving for himself shelter, food, and means for the latest improved firearms and ammunition when he occasionally returned from his lengthy and arduous pursuit of the enemy.

From that point on, John Joy Sr. was solely focused on one thing: revenge. His all-consuming desire for revenge seemed to possess him, and he avoided the company of others, often traveling alone. Sometimes he walked, but more often he rode, typically mounted on a tough Spanish horse that was both fast and hardy. This horse was almost unyielding; it would never tire, and it would never give in. He didn't allow strangers to approach him, and he was always ready to defend himself with his trusty rifle, which was always close by. This horse had a deep aversion to Indians and would detect their presence from afar. John Joy Sr. was known to camp alone in the wilderness, and if an Indian came near during the night, the horse's alertness, snorting, and stomping would warn him of danger.

Over the years, John Joy Sr. became a skilled practitioner of Indian woodcraft, developing an uncanny ability to spot signs of their presence—whether it be a freshly turned stone, a broken twig, or a crushed blade of grass. His activities and endurance seemed superhuman. One day he would be atop one of the Twin Mountains on the Concho, scanning the plains and distant horizons for smoke from signal fires; the next day, he would be on a high peak overlooking the San Saba Valley. The day after, he would be meticulously examining the watering holes along the upper Llano, in valleys, on hills, in mountains, and among cedar brakes. He was a phantom of grim tragedy, a silent and ghostly Nemesis who never slept, always alert, moved by a single relentless impulse: revenge. Such was the veteran John Joy Sr.

It appeared as if this determined old pioneer had gained the power of omnipresence, as stories circulated of how he was always on the trail of every band of Indians that raided the region from the Guadalupe to the Colorado. Any Indian who ventured into that vast territory often found himself being pursued by an avenging Nemesis. John Joy Sr.'s steady aim never faltered, and his trusty rifle never fired in vain.

At one point, while returning home from a long scouting mission in the Llano region, and when he was just a few miles from his ranch, his keen eye spotted Indian sign. Upon closer inspection, he discovered the trail of three Indians who had passed on foot in the direction of the Taylor ranch. He silently and swiftly followed their tracks, which led him west of the Taylor ranch and across a divide. On the second day, at nightfall, he unexpectedly came upon them in their camp, nestled within a cedar brake along the banks of a small stream. They had shot a cow and were enjoying roast beef when a shot from his rifle struck one of them in the heart, setting off a deadly firefight. In the end, all three Indians were killed.

One of the Indians, a woman, survived for a short while, gravely injured. While the Texans did not recognize her language, her agony was apparent, and she was given a drink of water. She soon succumbed to her injuries. John Joy Sr. collected six scalps, six bows, six quivers of arrows, and a few trivial Indian belongings.

After this incident, around 1864, the Taylor and McDonald ranch was established on the Pedernales River near Harper, Texas, approximately ten miles from Spring Creek. It seems that after his marriage, Monroe McDonald lived with or near his father-in-law, Mr. Joy, in Threadgill, which was several miles from the Taylor ranch.

During these challenging days, clothing for these pioneers was either homemade or traded, sometimes both. Spinning wheels, weaving blades, and warping bars were indispensable tools in every frontier household.

A few years after Mrs. McDonald's release from captivity, she married Peter Hazlewood. Unfortunately, during one of the last Indian raids in Gillespie County in 1872, Mr. Hazlewood was killed in a fight with the Indians on Spring Creek. Seven or eight years later, Mrs. Hazlewood married again, and at the latest reports, she was living in Ingram, Kerr County.

When the Indians, laden with stolen goods securely packed on horses, departed, Mrs. Hannah Taylor left the ranch in confusion and distress, not knowing where to turn. The following day, the folks at the Loss ranch, about twenty-five miles away, were startled by the appearance of Mrs. Taylor. Her frail shoes were worn from the rocky ground, her feet bled from numerous cuts and abrasions, her hands, arms, and face were covered with blood from contact with cactus and other thorn-bearing bushes. Her clothing was in tatters, and only remnants clung to her battered body. Her mind had temporarily succumbed to the ordeal, and she spoke incoherently, much like a child, occasionally breaking into fits of maniacal laughter in response to questions from the caring ranch people who quickly realized her misfortune.

In her time of need, the settlers rallied to provide her with care and attention. After many months of suffering, she eventually recovered and lived to an old age. Her husband, Matthew Taylor, was a Methodist circuit rider, and after her traumatic experience with the Comanches, she felt a divine calling to the ministry. She followed this call, becoming a preacher after professing sanctification and joining the holiness movement. Her fervent sermons were delivered at camp meetings, where she often erupted in shouts of praise and thanksgiving to the Lord for her deliverance. Her common expression during these shouts was, "Bless the Lord, the Injuns got me, but I got away agin'."

Matthew Taylor, her husband, led a life filled with hardships and challenges. He witnessed the transformation of the Texas frontier and the struggles faced by pioneers as they settled in the vast and often dangerous landscape. Despite the constant threat of Indian raids and the harsh conditions of frontier life, these settlers persevered, finding strength in their faith, their families, and their determination to build a new way of life in the Texas wilderness.

352 complete issue FLASH DRIVE, for only $89.95.

FOR A LIMITED TIME: $49.95 !!!

(plus, we will throw in 12 hard copy issues - FREE)

All the stories you could ever read! Click here!

20,000+ more pages of Texas history, written by those who lived it!

‹ Back

Comments