By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

Tribute to Jesse Chisholm - T. U. Taylor, Austin, Texas

[From J. Marvin Hunter's Frontier Times Magazine, July, 1939]

Jesse Chisholm died at Left Hand Springs on March 4, 1868, five miles east of Greenfield, Oklahoma. He had been in the northern part of Blaine county at the salt springs, converting the brine into salt and on returning with James R. Mead, P. A. Smith, and Joe Van (colored boy) he camped on March 3 at this historic spot, Left Hand Spring. It was the famous camping ground and there were many Indians there at that time. A bear had been killed and its meat was cooked in a brass kettle and everyone ate their fill. Jesse Chisholm during the night contracted an aggravated case of ptomaine poisoning and there were no doctors within 100 miles. He died early March 4, 1868. His home was over 59 miles away and there were no roads, only trails, and no means of rapid travel and no embalming process. The friends decided to bury him in the old Indian burying ground at Left Hand Spring. James R. Mead in his Memoirs stated that they buried him on the knoll near the spring and no directions and no measurements were given. In 1930 Joseph B. Thoburn, the late Alvin Rueker, and the writer visited this Left Hand Spring and marked a spot as the probable resting place of Jesse Chisholm. In December of 1930 the history class of the Greenfield High School erected a wooden cross and had it lettered on the mound in his memory.

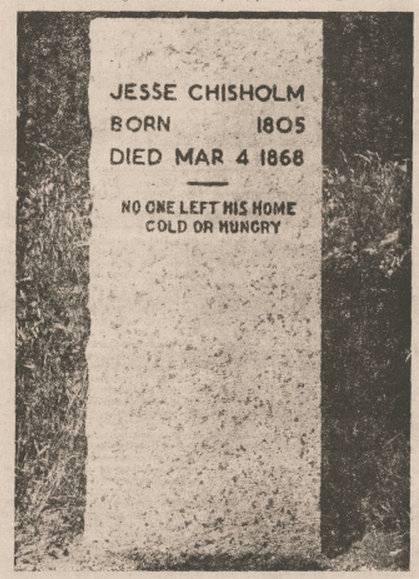

In the early months of 1939 the writer learned that this cross had deteriorated to such an extent that the grave was no longer visible from a distance The writer consulted an old pioneer of the Southwest, and they undertook t o erect a granite marker on the selected spot at Left Hand Spring. The quarries at Austin contributed the stone. The firm of Driscoll and Moritz did the lettering free of cost. Dave Dillingham contributed the car to carry the marker 451 miles and the writer paid for the gas and other expenses. The gravel and sand for the concrete base were shipped from Austin, and on Saturday afternoon, April 29, 1939, at 4:00 o'clock we began excavating for the foundation. The cement was bought at El Reno, a point on the old Chisholm Trail. The cement, sand, and gravel were mixed in proportions of 1-3-5, and Dave Dillingham, the old pioneer freighter in Texas, demanded that he be allowed to carry the water to mix the concrete from Left Hand Spring some 150 feet away, uphill all the way. The mixers really kept him trotting. The concrete was mixed by James Cooper and Billy Weizbrod of Greenfield, and the following four lifted the place, plumbed, resting in its bed of concrete: T. U. Taylor, Dave Dillingham, James Cooper and Billy Weizbrod.

By 5:30 p. m. the monument was in concrete. In the meantime six neighbor boys had collected, and over the monument Dean T. U. Taylor delivered the following address:

"Pioneers of the Southwest:

"We have met here today to pay homage to a remarkable character, who died at this spot some 71 years ago. This is an historic spot, well-known to the redmen long before the Anglo-Saxon passed up the valley of the North Canadian. Ere the Pilgrim Fathers landed on that historic rock, this old spring, now known as Chief Left Hand Spring, was gurgling and chattering its way to the sea. Here gathered the redmen to slake their thirst, rest their steeds, and hold their powwows, and here the pipe of peace was passed around the magic circle. When Washington crossed the Delaware, and when Sam Houston charged over the ramparts at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, this old spring was singing its song of gladness and goodwill, and slaking the thirst of the weary. When the first redman came to this valley, he found a primeval forest and a welcome murmur from this historic spring.

"To this place came the weary tribes from the chase, and here caravans of the Saxons found a place to pause and rest. From Fort Smith to Santa Fe the fame of this old spring was spread along a trail over 800 miles in length almost due west. Here many an old square dance was called by some pioneer while the old fiddle screemed the melody of 'Cotton Eyed Joe', "Turkey in the Straw', or 'The Arkansas Traveler'.

"Red man and white man came here as a rallying point to rest, trade, or form treaties. If these trees could talk, they could tell a story of the ages where the fierce Comanche met the sedate Cherokees.

"Here came Jesse Chisholm on his way to the Salt Springs of Blaine Bounty; and here he gave up his life on March 4, 1868. This old spring still sings its song to the people of Oklahoma, and like it, the life of Jesse Chisholm still holds away in the affairs of men in this new commonwealth. Jesse Chisholm met and came to know characters of the old Indian Nation and died before seeing his dream of a great commonwealth born into the American Union. Without any advantages of youth, he rose to be a great factor in the affairs of the Old Indian Territory. From 1828 to the day of his death within a few feet of where we are now gathered in his honor, he was first in the hearts of the Indians, whether it was the peaceful Cherokees or the warlike Comanches. He was a foe to graft and greed, father to the orphan, a friend of all men, regardless of color, founder of the bold Chisholm Cattle Trail. In the records of the U. S. Army at Washington many are the tributes paid by the officers to the wisdom, integrity, and sterling character of Jesse Chisholm.

"In his veins flowed the blood of the Scottish Highlander, and of the Cherokee Indian; and he inherited the best traits of both peoples. In honesty and integrity, he reflected that of his forebears of the hills and old Scotland, and on his mother's side he reflected the ideals of the Sequoyah, the Rosses, and the great chiefs that spoke with a straight tongue. Fourteen tribes welcomed him as a brother; 14 dialects he spoke to the redman, and he sat at council with the great officials of the White Father. He was the one man to whose voice everyone paid heed, whether it was the fighting Comanche, or an officer of the U. S. Army. In wigwams and in barracks where Jesse Chisholm sat was designated as the head of the table. The Comanche would have no interpreter other than Jesse Chisholm, and at Comanche Peak in Hood county, Texas, in 1846, they refused to enter the council because Jesse Chisholm was not present. Representatives had to be sent to Edward's store and their friend brought to act as an interpreter before they would enter. Two months later, the treaty of 1846 was held seven miles northeast of Waco, Texas, on Tehuacana Creek.

"In his veins flowed the blood of the Scottish Highlander, and of the Cherokee Indian; and he inherited the best traits of both peoples. In honesty and integrity, he reflected that of his forebears of the hills and old Scotland, and on his mother's side he reflected the ideals of the Sequoyah, the Rosses, and the great chiefs that spoke with a straight tongue. Fourteen tribes welcomed him as a brother; 14 dialects he spoke to the redman, and he sat at council with the great officials of the White Father. He was the one man to whose voice everyone paid heed, whether it was the fighting Comanche, or an officer of the U. S. Army. In wigwams and in barracks where Jesse Chisholm sat was designated as the head of the table. The Comanche would have no interpreter other than Jesse Chisholm, and at Comanche Peak in Hood county, Texas, in 1846, they refused to enter the council because Jesse Chisholm was not present. Representatives had to be sent to Edward's store and their friend brought to act as an interpreter before they would enter. Two months later, the treaty of 1846 was held seven miles northeast of Waco, Texas, on Tehuacana Creek.

"Chisholm traveled at least four distinct trails over the terrain of the old Indian Nation. First, he was in the party that marked the road from Fort Smith to Fort Towson, that was cleared and constructed by the U. S. soldiers in a few months as a commercial and military highway. Second, in 1836, he traveled the route from the old Chisholm Spring to the Arkansas River, where later the town of Wichita was located. Third, he traveled from Fort Gibson to Edwards—the Chisholm Spring to Choteau near Lexington— to Council Grove, a few miles west of Oklahoma City. Then in 1865 he traveled the route later called the Chisholm Trail, then to the Salt Springs in Blaine county; and last, from these salt springs to this very spot, where after threescore and ten and one years we pay a belated tribute to his memory.

"Throughout his active life Jesse Chisholm was a Good Samaritan in the Indian Nation. For forty years, from 1828 to 1868, there was no record of his passing by "on the other side of the road," and leaving a wounded man helpless by the wayside. Giving immediate help with no thought of reward was his creed. Such action came as natural to him as breathing does to us. It was part of his life. Jesse Chisholm traveled many roads in Oklahoma, Kansas, and Texas, and he found many helpless, and in hundreds of cases he gave a helping hand. No hungry man ever went from his door unfed. He asked no names, expected no reward, and respected no colors of skin, but fed them all. Some of each color served him and his family throughout their lives and would not leave for `fatter fields' out of gratitude.

"He was a trader for 40 years, and in all his dealings with men of all colors and all creeds there was never a dirty dollar in his fortune. He ran a department store on wheels or on pack saddle. He had all his goods classified, and he has the record of organizing the first department store on mule back in the world.

"The greatest honor paid to Jesse Chisholm during his life was paid by the fierce Comanche chiefs. In gratitude for his services through a quarter of a century, they presented to him a silver bracelet. This bracelet was given by Jesse Chisholm to his wife, Sahkahkee McQueen Chisholm, and by her to her daughter, Aunt Jenny Davis, who died in 1930 at the age of 82, and now sleeps on the banks of the North Canadian, four miles south of Paden, Okfuskee county. Aunt Jennie gave the bracelet to her son, Alfred Harper, who is living today near Wewoka.

"We pay tribute today to Jesse Chisholm, but our tribute is feeble when compared with the tribute paid him at his death in March, 1868. Picture with me the scene at the day of his death on this spot 71 years ago. There were camped some of the Indian tribes, and when they learned that Jesse Chisholm had died, swift runners carried the news from the valley and from tribe to tribe. Old settlers have told me that all the Indian tribes in Oklahoma went into mourning when they found that their best friend, their father confessor, had passed away. The tomtom beat in the tribe of the Cherokees in the east and the fierce Comanches tore their flesh and beat their rude drums in the west. No man in Oklahoma has been mourned by as large a per cent of the populace as was this man who was of and for the people. His blood flows in the veins of seven living grandchildren, three granddaughters, and four grandsons—five of whom are living in Oklahoma today.

"He left a record of forty years of square dealing, of helping the poor, and befriending the outcast. He was true to the American flag, and he protected the homes of the whites from the red warrior who thirsted for revenge. There are people living today in Oklahoma whose grandparents lives were saved by the timely and swift action of this man of peace, the only man who ever lived in this commonwealth that could go without escort, unarmed, from Fort Gibson in Eastern Oklahoma to Fort Stockton in Trans-Pecos, Texas, without the slightest danger to his person from white, red or black man. His life is concentrated in his creed:

"No man ever came to my door cold and went away unclad: no one ever came to my door hungry and went away hungry.

"This granite marker is placed here resting in broken fossils of limestone of ages past; the sand has been washed hundreds of miles from down the gorges of the river, and the cement is made from the clay over which Jesse Chisholm stood, and the water that cements and solidifies this base into one everlasting monolith comes from the Chief Left Hand Spring, where Jesse Chisholm died—near where you are now standing. His body rests in the soil of his adopted commonwealth and his memory rests in the hearts of his countrymen.' "

We returned to Greenfield and in the streets we ran into an Apache Indian. On being told that we had just erected a granite monument to Jesse Chisholm, he folded his arms and in about eight words gave the finest biography of Jesse Chisholm ever written or expressed:

"Jesse Chisholm. Fine man! Good man! Great man!”

‹ Back