By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

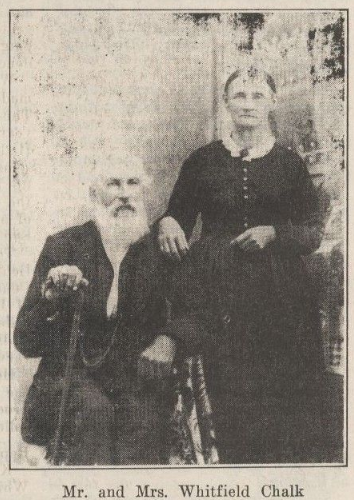

The Story of Whitfield Chalk - By Houston Wade

[From J. Marvin Hunter’s Frontier Times Magazine, November, 1940]

The information shown here really belongs at the beginning of this biography, but as is always the case, the printing of the story as already shown brought to light additional information. In order to make our work as complete as possible, and in order to do justice to our readers and our hero, we are of the opinion that it is no more than right for us to show data subsequently located.

All the information shown below comes to us from Mrs. Sarah Minna Chalk Hyman, who has spent much time and effort in tracing the Chalk line back to its very first beginning. She has made a trip to England in quest of authentic records preserved in the archives of London and elsewhere in the English islands. She had thoroughly gone into our own Colonial and Revolutionary records from earliest time of the period of 1776 and before. We will now quote directly from the records of Mrs. Hyman:

From Collinson's History of Somersetshire (England), we find that the Chalk family was in England before the Norman Conquest of 1066. The name Chalk most likely is of pure Saxon origin and men of this name may have fought with Harold, the last of the Saxon kings, at the decisive battle of Hastings.

Sir Richard Chalk was one of the Justices of the Common Pleas and later Chief Justice of England during the reign of Richard III. The family became hopelessly impoverished by the heavy fines levied on them for the crime of adhering loyally to King Charles I. Here is the description of the family coat of arms: Out of a Ducal Coronet or a domi-Swan, arising argent, crested guloo. Motto: "Semper Virtute Vigo" (Always live by virtue).

The family of Chalk owned and came from "Chalk Farm," once a suburb, but now in the heart of London, England. William Chalk, the grandfather of Whitfield Chalk, was a sea captain and owned his own vessel. His ship carried cargoes between the home port of London and the West Indies.

After coming to the United States (then an English colony) he took part in the American Revolution. After the war he went to sea again, where his ship and all on board were lost during a storm. This catastrophe occurred just off the coast of North Carolina, in sight of land and his wife and children witnessed the sinking of the boat.

William Chalk, grandfather of Whitfield Chalk, was a private in Captain Tatum's company, Tenth Colonial Regiment. He enlisted December 29, 1776, and served three years. Was promoted to Sergeant in March 1780. From the Department of State, North Carolina, comes this additional record: Member Howell Tatum's Company, First North Carolina Battalion commanded by Colonel Thomas Chalk. This roll is dated September 8, 1778. The war Department, Washington, D.C., shows that William Chalk joined the army December 29, 1776, which verifies the state records.

The maiden name of the wife of Captain William Chalk, the sea captain, was Peggy Askew. She was a direct descendant of the family of Anne Askew, the Martyr, who was burned at the stake during the reign of the muchly married Henry VIII. As usual the first thing to do about this hero is to prove what his name really was. This is the same man that Thomas Jefferson Green lists on page 438, item No. 49, as Winfield Chalk. On page 445 of this book he repeats the error and again spells this name "Winfield," which is pretty close for Colonel Green. This is not all of the Green errors; he states that Mr. Chalk and a man he shows as Caleb St. Clair were the only two to escape from Mier "on the evening of the capitulation." Subsequent findings have shown that this statement of Green's is not correct either, because we have proof positive that Michael Cronican, a hero of San Jacinto, made his escape from Mier at the same time. Worse than that, Green fails to mention Michael Cronican in any way or in any part of his book, and yet he was there and took an active part in the battle of Mier.

The name of Michael Cronican is properly shown on the original muster roll of Captain Charles Keller Reese, and this muster roll adds further this interesting information concerning him: "Killed at the Battle of Mier." For a long time we accepted this statement as true; however, in reading the proceedings of the Grand Lodge of Texas Masons, we discovered where he had represented Harmony Lodge No. 6, of Galveston, in the Grand Lodge. As it was impossible for him to have been killed December 25, 1842, and represented Harmony No. 6, A. F. & A. M., February 17, 1846, we decided to go further into this matter. The result of our deduction is that Mr. Cronican, who was a newspaper man and evidently a fast thinker, must have lain down among the dead. smeared a little blood on the side of his head, and played 'possum, which accounts for the entry on the muster roll showing him killed in action. His comrades are bound to have seen him under circumstances that led them to believe him dead. After the prisoners were marched away to be confined, Mr. Cronican was left alone with his dead; then he calmly arose and walked away and made his escape. Americans are noted for quick thinking in emergency cases and this is a beautiful example.

And another thing: Thomas Jefferson Green refers to the man who escaped with Whitfield Chalk as Caleb St. Clair. As a matter of fact, so far as the authentic records go to show, there was no such preson as Caleb St. Clair. This man is listed on the muster roll as William St. Clair and attached to the claim of the Yocum family for the death of little Jesse we find his signature, and it too, shows William St. Clair. Chalk up still another error on Col. Green.

Now we will get back to our hero.It is curious to note that on the original muster roll this name is shown as Charles Chalk. The orderly sergeant, Peter Menard Maxwell, who made out this roll, is bound to have been something of a stranger to Mr. Chalk, or he would not have made such a glaring mistake.

For the benefit of our readers, we will say that we were fortunate in locating a living son of Whitfield Chalk. He is Captain Martin P. Chalk of McAllen, Texas. From this source much of the information below is derived. We mention this to show that our statements are authentic. Captain M. B. Chalk followed the footsteps of his illustrious father and served for a time as a Texas Ranger, 1884-1891.

Whitfield Chalk, the subject of this sketch, was the oldest son of William W. and Mary W. Chalk. His parents had sailed from England shortly after their marriage. They landed in America in January 1811, and settled in the State of North Carolina, where their first son was born April 4, 1811, about two weeks after reaching the old North State.

Information concerning our hero is necessarily fragmentary and obtained from many sources. About the life of our hero during his boyhood days we know little; however, we gleaned one interesting item, which we reproduce below just as it appears in print:

"When Whitfield Chalk had reached the age of twelve years, the family moved to Tennessee, (1823). The death of his father a few years afterwards caused young Chalk to turn his eyes also towards the West....

"On his trip down the Mississippi on one of the old steamboats, Mr. Chalk had a rather unusual experience. Crew and passengers were attacked by the cholera and all of them, with the exception of Chalk and the captain of the old craft died."

(Source: Frontier Times, V. 1, No.2, p. 23).

From the above account the fact is evident that Mr. Chalk left for Texas alone and although he had at least four brothers, none of them seems to have been with him on his first trip to the Republic of Texas.

The names of these four brothers were John Wesley, named for the famous divine; William Roscoe, named after his father; Ira Ellis and Josiah Chalk. All four of these brothers were ordained Methodist ministers and it was John Wesley Chalk who had the distinction of having preached the first Methodist sermon in Fort Worth. It is a fact that all four of these brothers came to Texas, but when and how is not known to the writer.

The date of the arrival in Texas of Whitfield Chalk is a much disputed point, and we have had at least three different dates offered to us as correct; however, we find that in 1873 our hero made application to join the Texas Veteran's Association, and this application made out by Mr. Chalk himself reads as follows:

"Chalk, Whitfield—Second Class, age 63, nativity, North Carolina; emigrated in 1839; served in the campaign of 1812; Mier prisoner, residence Lampasas County."

We are accepting this statement made by our hero himself as correct. This shows that he was twenty-eight years of age when he came to Texas. Had he arrived as early as 1833 as some claim, he is bound to have shown up in some of the stirring events of the days of 1836. There is no record of any service rendered by him in the San Jacinto campaign.

To the best of our knowledge Whitfield Chalk settled first in Milam County, or at least in that huge piece of land that was then known as the Milam Land District. Twenty-four additional counties have since been carved out of the land district.

He was living there when he joined the army the second time, and in proof of this statement we submit the follownig affidavit:

Republic of Texas,

Know all men by these presents that Whitfield Chalk was duly enrolled in my company of Mounted Riflemen on the 17th day of October 1842, and fought bravely in the battle of Mier on the 25th and 26th of December, A. D., 1842, and after the battle made his escape and is hereby honorably discharged from the service of Texas. Given under my hand this 16th day of September, 1884.

J. G. Pierson

Capt. Mounted Riflemen.

We have no evidence that would lead us to believe that Mr, Chalk participated in the Vasquez Raid; however, we have his own statement that he took part in the Woll Invasion. This being true he is bound to have made a flying trip to San Antonio the previous September and on the advice of Edward Burleson returned home to equip himself properly, and report to headquarters later for participation in the Somervell "Wild Goose Chase" which was the prelude of the Mier Expedition.

We ran across an interesting description of the personal appearance of our hero, as a friend of his saw him just about this time. Here is what he looked like:

"Whitfield Chalk was a tall, dark haired and grey eyed man, with a fighting jaw on him; he was six feet tall, well proportioned and of deliberate speech and movements, showing determination and resistance in every act—the very type of a brave determined man and clearly portraying he would do what he did do."

(Source—Newspaper clipping December 1911, by John Dowell, Houston. In collection of Dr. Alex Dienst of Temple.)

As we have already seen, Whitfield Chalk joined Captain J. G. W. Pierson's company of mounted riflemen on October 17, 1842. This body of men later became Company "D" of the Mier Expedition. It was composed of twenty-seven men in all. J. G. W. Pierson was the Captain: Whitfield Chalk was Lieutenant, and Peter Menard Maxwell was Orderly Sergeant and made out the roll. Three of these men were left on the Texas side of the Rio Grande as part of the camp guard detail. Little Jesse Yocum was killed before the fight started, so that left only twenty-three men who participated in the fight.

Captain Pierson and his men left for the front on horseback. This we know because he called them mounted riflemen, and from the further fact that the survivors made claim for horses and equipment lost. The claim of Mr. Chalk reads as follows:

Late Republic to Whitfield Chalk, Dr. To services of the Mier Expedition

(Engaged in the fight and made his escape after the surrender)

in service about three months at $22.50….$67.33

Horse and equipment lost…………….…....$65.00

_________________________________________

…………………………………….………….$132.33

(Source: Public Debt Papers, State Library, Austin).

We will not repeat the story of the Somervell Expedition or the battle of Mier. To do so would consume too much space and is not necessary to this account. We refer our readers to the book by Thomas Jefferson Green for a detailed account of what happened. Sufficient it is to say that the companies of Captain James Keller Reese and Captain J. G. W. Pierson were a part of the left wing of the Texas forces that captured the town of Mier and that they saw plenty of action and acquitted themselves nobly. Our interest now is in the escape of our hero, and here is shown another example of quick thinking on the part of this American soldier.

There are many versions of the escape of Whitfield Chalk and William St. Clair from the Mexicans after the surrender at Mier; however, these stories are all similar and differ only in detail. We will reproduce here only one of these accounts; the one that seems to us to be the most reasonable and interesting and of the most historic value. For the benefit of our readers, we will explain that after the Texians had been tricked into surrendering and parting with their arms, they were confined in low, dobie houses, and in transferring our men from one of these huts to another for convenience and safety, our two heroes decided that they did not relish being prisoners in Mexico and proposed to do something about it.

From here on we will let others better qualified tell the story of the escape: "The night of the capture of the Texians was stormy, and an impenetrable darkness prevailed. Though the prisoners of war had no inkling then of what their fate was to be, Whitfield Chalk and one other member of the expedition thought it well to attempt escape. On their way to some huts that were to shelter and guard them for the night, Chalk and his companion quietly slipped out of line and concealed themselves under some sheaves of corn stacked against the wall of a small building.

"Had it been daylight the men would have been found by the Mexicans without much trouble, as their feet protruded from under the stalks. It is also possible the Mexican soldiery concluded that the missing prisoners could not escape anyway, and that for this reason they did not make close search as they would have done otherwise. At any rate Chalk and his companion succeeded in reaching the open country beyond the camp of the Mexicans.

"All night long they pushed through the dense chaparral. Though both were nearly exhausted, there was nothing to do but put as much distance between themselves and the Mexicans as possible. It had been the dry season of the year. The ground showed many a wide, gaping crack. Into one of them now and then would stumble the weary feet of the fugitives. Before long both of them had lost their shoes. Distance, they knew, was the only thing that would save them, and seconds, therefore, were precious. Moreover, the shoes worn by them were too large and heavy, and since safety lay in flight and sore feet could be healed, they decided to do without them. Later they regretted having left their shoes behind, but it was then too late to get them back. Finally they reached the camp of the Texian forces and rejoined them."

(Source:—Frontier Times, V. 1, No. 2,p. 23. Nov. 1923.)

This ends the quotation that we think was dictated by Whitfield Chalk himself. And now we are most fortunate in having a most celebrated man take up the story exactly where our hero leaves it. This man was no other than George Bernhard Erath,—the man for whom Erath County is named. How strange it is that Thomas Jefferson Green could have had a man so prominent as Mr. Erath in his command and not know it. It is a fact that in the entire book written by Green he never once mentions George B. Erath, and yet it is Mr. Erath who left us the only account of the events that transpired on the Texas side of the Rio Grande while the battle of Mier was in progress. Now we will let Mr. Erath take up the story where Mr. Chalk leaves off. We will only add that Lieutenant Chalk was slightly wounded in the arm during the fight:

"At nine the men became anxious to go on. I went back to hunt Pierce, knowing that the men would not go without me. I had not gone over 300 yards before I heard talking in the brush on my left. I turned thither and found about a dozen of the men we had left in camp the night before, and with them two of my mess-mates escaped out of Mier, (Whitfield) Chalk and (William) St. Clair. We all returned to my party of men, and delayed for Chalk and St. Clair to eat something; they had been long without food

"St. Clair was one of those who wanted to fight his way out (of Mier), and he determined to escape somehow. He induced Chalk to hide with him behind a bunch of cane stacked in a corner of a room where they with others were confined. After nightfall they slipped out of town. In jumping a wall St. Clair sprained his ankle and was badly lamed. He had already lost one boot; it had been pulled off by a Mexican as he got over a fence going into Mier. They finally reached our camp on the river at daylight. The men took a boat over to them, and then all the men in camp, except (George W.) Bonnell and Hicks left, each with two horses."....

"After we reached and crossed the Nueces we separated into small parties, the better to find game, which was scarce except for wild horses. Chalk, St. Clair and a young man named (Thomas) Oldham remained with me, and we four were the first to arrive at the San Antonio River, at Goliad, then unoccupied. The diver was swimming. We saw six men over on the other side who had just crossed on a raft of logs and door drifted down from houses above."

"We all reached Lockhart's house the next afternoon, obtaining supplies of eatables, crossed the Guadalupe River the next day in a canoe, swimming our horses, and separated. Chalk, Tom Oldham and I crossed the Colorado at LaGrange, bringing to that place the first news of the defeat, and reached home on the 19th of January, 1848." (Source: Vol. 27, S. W. Historical Quarterly.)

Now that we see that our hero is well out of the scrape he was in and safely back home from his great adventure of the Mier Expedition, we will try to follow the thread of his life as far as we are able and the records will permit.

Home to him is still evidently the huge Milam county, and for about a year there is little or no record of his actions. It may be that it was at this time that he served his enlistment with the Texas Rangers, under Captain Sul Ross. We know that he did serve in at least one campaign, but we have never been able to establish the dates.

Sam Houston had many faults; he also had some virtues. One of these outstanding virtues was his custom of rewarding his old comrades and deserving friends with positions, commissions, jobs and places of trust in his government. It has often been said that he retained enough of his Indian influence never to forget a friend or forgive an enemy. He most certainly was a true friend to many and a first-class hater of those who opposed him.

Whitfield Chalk being now a veteran, an efficient officer and a person of trust, President Sam Houston selected him as a fit object on which to bestow an army commission. This document still exists and hangs in a frame in all of its glory, in the home of his son, Captain Martin B. Chalk, who kindly supplied us with a copy of it which we will now show:

"IN THE NAME AND BY THE AUTHORITY OF THE REPUBLIC OF TEXAS. To all who shall see these presents.

GREETING:—Know ye. That I, Sam Houston, President thereof, reposing special trust and confidence in the patriotism, valor, fidelity and ability of Whitfield Chalk, do hereby commission him a Major of the Second Regiment of the First Brigade of the Militia of the Republic of Texas, in conformity with an act of Congress, Approved 24th January 1839.

"He is, therefore, carefully and diligently to discharge the duties of Major by doing and performing all manner of things thereunto belonging. And I do strictly charge and require all under his command to be obedient to his orders as such.

Given under my Hand and the Great Seal of the Republic at Washington-on-the-Brazos this fiffh day of August in the year of Our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and forty-four and in the Ninth year of the Independence of the Republic of Texas. By the President, SAM HOUSTON, C. W. Hill, Secretary of War and Marines."

We see that his commission, shown above, is dated only a little over a month before the remnant of his comrades of the Mier Expedition were finally released from prison in Mexico.

Sam Houston laid himself open to much criticism on account of the indifference with which he viewed the fate of the Texas prisoners. This attitude earned him the violent hatred of many of the Mier Prisoners, but some were still loyal to him.

So far as we have been able to ascertain, Whitfield Chalk was one of these, and held his commission in the army as a Major from 1844 to about 1847; rendering excellent service and earning for himself the respect and admiration of the people of Milam County.

It must have been sometime while he was a dashing Major of the Mounted Militia of the Texas army that romance crept into his life, for we find that on August 9, 1847, at a small settlement at the old Double File Crossing of the San Gabriel River, about four miles east of the present village of Georgetown, he took unto himself a wife in the person of Miss Mary Fleming and it was on this spot that the couple set up housekeeping.

Some historians have set up the claim that Major Chalk was married twice. Here and now let us correct this error. He was married only once and remained a true and faithful husband and father all the days of his life, and it was only death that separated him from his beloved Mary, the mother of his nine children. We give reason for his resignation was that he was to be the first sheriff of the newly-created Williamson County. This county was carved out of the Milam Land District in March 1848, but it was not until the following August that it was properly organized. We see from this that he was made sheriff just about the time he was made a bridegroom. We do not know for a fact how long Major Chalk served high sheriff of Williamson County; however, it could hardly have been more than one term.

The next authentic trace we have of our hero is extracted from the records of the First United States Census taken in Texas. These reports read as follows and are for Bell county:

"Chalk, Whitfield—occupation, millwright, age 39, born in North Carolina, wife Mary M., born in Georgia, children, William T., age one year, John W. age five months; both born in Texas."

From the above item it is seen that the Chalk family have moved to the newly created Bell County, but still in the old Milam Land District. Bell County was created in January 1850, but was not organized until August, 1850. From this census report we also learn that Major Chalk's wife was born in Georgia and that her middle initial was M., and that he now really has a family, for two children have arrived to bless his married life.

Now we will have to turn to the information shown in the new "History of Bell County," written by the distinguished George W. Tyler in order to locate the place of residence and business of the subject of this sketch. This history has the following to say concerning him:"

The first mill (in Bell County) was probably that of Ira Chalk and Whitfield Chalk, begun on the Salado in 1849 and later known as the Ferguson Mill."

The above item discloses that Major Chalk and his younger brother Ira Ellis Chalk, have erected a sawmill on Salado Creek, near the little city of Salado, now a ghost town of Texas. It also shows that one of his brothers has followed him to Texas. A second brother, William Roscoe Chalk, lived for several years at Belton, in Bell County. The Chalk mill was later equipped to grind grain as well as saw lumber and was operated by waterpower. It was acquired by the father of Governor James E. Ferguson and later was known as the Ferguson Mill.

This brings us to the year 1857. Texas is now no longer a Republic, she has been the brightest star in the constellation of the glorious Union for about ten years. At the time Texas was annexed, she still laid claim to a strip of ground running north almost to the magnetic pole and west to include everything but the Pacific Ocean. Uncle Sam, to quiet those claims and to set up a boundary line, paid us a cool ten million dollars. This money the new State of Texas used largely to pay for the long overdue claim of the old veterans who had fought in the wars of the Republic and helped gain our independence.

The Mier prisoners were allotted an average of $605.00 as part compensation for the hell they had gone through between December 25, 1842, and September 16, 1844. From a look at the records it would seem that just about every old soldier still alive made a grand rush on this Court of Claims to file his papers.

We have already seen where Major Whitfield Chalk had asked for and received $132.33 for three months' service as a soldier and the loss of his horse and equipment. Now he comes forward and on December 28, 1857, files claim for $472.50 more, being the balance due of the allotted $605.00. This claim was paid. Major Chalk was still living in Bell County when this claim was paid.

By the year 1870 the State of Texas had passed a law granting a pension to the surviving veterans of the Texas Revolution. This law included an act for the relief of the Mier prisoners. Our hero, Major Chalk, decided to seek the benefit of this law and on December 13, 1870, filed his application for a pension with Hon. A. Bledsoe, State Comptroller. He was living at Brenham, Washington County, at this time.

It was here that Major Chalk ran into an unexpected snag. His application for a pension was promptly turned down for the technical reason that he was not a Mier prisoner and had never been confined in Perote Castle. That he had made his escape and for that reason did not come within the meaning of the law for the relief of the Mier prisoners.

It was here that his old Bell County friend, George W. Tyler, came to his rescue, and by a special act of the Legislature secured a pension for our hero. We take pleasure in quoting their names in the order in which they were born: William T.; John Wesley; Henry A., died at the age of 23 and is buried at Brenham; James M.; Mattie E.; Katie N.; Jeff D.; Jack, died at the age of two and is buried at Brenham; and Martin B. Chalk.

It is not clear whether Major Chalk resigned from the army before or after his wedding day; however, the below exactly what Senator Tyler has to say on the subject:

"Whitfield Chalk was a well known citizen of Bell County, whom I know personally. He escaped from the Mexicans after the surrender of Mier; returned to Texas, and was not confined in Perote. This fact technically excluded him from the benefit of the pension act, and while I was in the State Senate, I obtained his pension for him by an amendment to the general appropriation bill. (See General Laws, 21st Legislature, p. 77.)"

(Source: Extract from letter written by George W. Tyler of Belton, Texas).

By 1873 Major Chalk had removed his family to Lampasas County. This we know because his application for membership in the Texas Veterans Association is dated from that point. There is little more for us to tell about Whitfield Chalk and his family. He lived the remainder of his life at or near the town of Kempner, Lampasas County, and it was there he died on May 18, 1902. His beloved wife, Mary, survived him only a very short time. When she lost her mate, all incentive to live left her, and she passed to her just reward in January 1903. They are both buried in the cemetery at Kempner and the grave of Major Chalk was marked; however, the stone may have disappeared.

To set at rest the question of his wife, let us explain here that it was Ira Ellis Chalk who married the second time. The first wife of Ira E. Chalk was Miss Phoebe Fleming, a sister to the wife of Whitfield Chalk. Ira Chalk and his wife lived for a time with the family of our hero. He had three children by his first wife. Both families removed to Kempner and it was there that Ira Chalk married the second time. He had six children by his second wife.

In conclusion let us repeat that it is not well to examine too closely into the private lives of our celebrated men if an attitude of hero worship is to be preserved. Our tribute to this hero is that all evidence goes to show that he was a man far above the average in every respect. He was honest, brave and true. He was loved and respected by his nearest neighbors, a man anyone could be proud to call friend.

*************

20,000+ pages of Texas history on a searchable CD or flash drive. Get yours today here.

‹ Back