By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

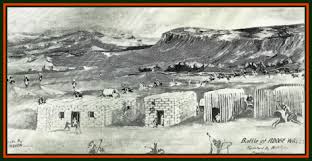

THE BATTLE OF ADOBE WALLS

From J. Marvin Hunter's Frontier Times Magazine, April, 1947

The battle of Adobe Walls, where twenty-eight straight-shooting plainsmen held five hundred Comanche Indians at bay for five days, and with their withering rifle fire finally brought conviction to the Indians that the scalps of the twenty-eight were not worth the price it would take to get them, is a desperate adventure of frontier days in the Panhandle of Texas.

John J. Clinton, who died at Abilene, Texas, June 1, 1922, and who at one time was Abilene's chief of police, took part in the Adobe Walls fight. Chief Clinton, in relating incidents of the battle, said it was the most thrilling experience in the more than half century of his life as frontiersman, Confederate soldier, government scout, cowboy, Indian fighter, Texas Ranger, and in the later and more placid days, peace officer in a prosperous and modern West Texas town.

Adobe Walls, the scene of the five-day battle, is now a small place in Hutchinson county, Texas, seventy-five miles northeast of Amarillo. At one time it was on the main route of an old cattle trail along which plains cattlemen drove their herds to market, at Dodge City, Kansas, before the railroads penetrated the great cattle ranges of the Southwest.

The fight occurred in 1874, at a time when the settlers gave little thought to the Indians. The warlike Comanches were assumed to be contentedly smoking their peace pipe s on the government reservation at Anadarko, in the Indian Territory, under the watchful eye of the commandant of the reservation fort. But aroused to a fanatical pitch by an Indian medicine man, a band of five hundred of these warriors, under the leadership of their chief, Sun Boy, had eluded the government troops and started on the warpath to the northwest, where cow-camps were plentiful, where there were many possible white scalps and much plunder.

John Clinton, with four Mexican vaqueros, was beating up the Panhandle, along a cattle trail, looking for a bunch of horses that had gotten away from him on his way back from Dodge City, where he had accompanied a herd of steers. Early in the morning one of the four Mexicans uncovered the broad trail of a large band of Indians and the little party, fully appreciating the situation, rode at top speed for the nearest place of safety. This was Adobe Walls, twenty-five miles to the northwest, where there was a small frontier camp occupied by a party of buffalo hunters. Thinking each moment they would be discovered by the Comanche scouts, and forced to stand where complete extinction might only be a matter of time, Clinton and the four Mexicans pushed forward rapidly and at sundown rode their exhausted horses into the camp of Adobe Walls.

Adobe Walls was more than a camp. It was a crude frontier fort. The walls were built of the material which gave them their name, adobe—thick at the base and tapering to twelve inches at the top. They were stockade height and plentifully punctured with loop-holes. Except for a broad entrance gap, they described a complete circle. Nothing but heavy artillery could have prevailed against them in hostile attack. Who built the walls no one knew. Old timers said Kit Carson once sought refuge in them from the Indians, and that there were many legends as to their construction.

Inside the walls, in rough timber shacks, the lumber for which was freighted out from Dodge City, Kansas, there was a saloon and gambling hall, store, and other equipment of a typical frontier gathering place for the devil-may-care male breed of the plains.

With the arrival of Clinton and his vaqueros, the total population of Adobe Walls camp was twenty-eight, and it was a strange collection of men of many different types and nationalities. Almost each man was a rank stranger to the other, but all were of the plains breed whose courage was never questioned and whose daring had been proved too many times to be doubted; each had the fighting instinct of the Anglo-Saxon developed to the highest pitch by the wild condition of the frontier. There were buffalo hunters with their curious rifles, seasoned Indian fighters, soldiers on furlough, trappers, gamblers, scouts, rangers, and camp hangers on, Americans, Englishmen, Germans, Mexicans, and what not. Each man with his brace of deadly six shooters and his cherished rifle, was a fighting unit in himself.

ENJOYING THIS STORY?

"There hain't been a Injun off the reserve for two years," was the scornful reply they had for Clinton's warning of the band on the war-path. The camp life went on with many joking references to "Clinton's Injins." That night Antelope Jack, a notorious frontier gunman, held a mysterious card in a poker game and got crossed up with a man who beat him to a draw. There was a quarrel, a flash of revolvers and a midnight funeral in camp; many of the remaining twenty-eight men, their serenity slightly ruffled by the tragedy drank heavily of liquor and were soon sound asleep.

In the middle of the night occurred the thing which Clinton believed was a supernatural agency to save them all from surprise and death. The ridge-pole of the earth roofed building, under which the men slept, broke with a crack that brought every man to his feet with weapon ready for any contingency. The camp settled down again, but the incident called for more drinks, and it was nearly morning when sleep was again thought of.

Clinton and Billy Dixon, an experienced Indian fighter who had been impressed with the story about the Comanches being on the war-path, decided to remain awake the balance of the night. They took their blankets to the stockade and sat smoking their pipes with their faces to the prairie which sloped up to a long ridge before the Walls.

Just before dawn they observed a moving blur on the crest of the ridge. Their field glasses revealed the riders. They were Comanche Indians and were mobilizing for an attack on Adobe Walls.

The alarm was sounded and all entrances quickly barricaded with boxes, barrels, and every movable thing that would offer resistance to a bullet. When the five hundred red men swept over the hill in their first charge, with the indescribable yell that has made the name of Comanche synonymous the world over for diabolical deeds, they were met with a withering fire that sent them reeling backward, but not before they had thundered to within a few feet of the Adobe Walls. This was first of many charges, usually just at dawn and at dusk, in the long five-day battle that followed.

None of the defenders thought for a moment that the Indians could storm the Walls, yet their food and ammunition grew scanty. The Comanches, maddened by losses and incited to frenzy by the supernatural incantations of their medicine man, raged about the Walls, vainly endeavoring to batter down the defenses. At each charge they would be met with the deadly rifle fire of the frontiersmen who were well protected by the thickness of the Walls.

At last the defenders decided that the medicine man must be disposed of. This was an undertaking for desperate, but brave men, for the medicine man was crafty enough to drop back after he had led each charge almost up to the Walls. He was always accompanied by a negro bugler, who had deserted from the Ninth United States Cavalry. Disposing of the medicine man and his negro bugler, who inspired the red men to battle by incantations and improvised bugle calls, was left to a party of five volunteers—Clinton, Dixon, two Shadley brothers, and a man named Tyler. These five men, on the fifth night of the attack, crept out of the enclosure and crawled to a wagon two hundred feet from the main entrance to Adobe Walls. Here they lay until daylight, awaiting the usual Indian charge.

As the first glow of dawn over the hills came the medicine man on a big white horse, the negro bugler at his side, and the entire army of red men at his back. On the crest of the ridge he paused, made a few "awe-inspiring" gestures, and signaled the negro to sound the charge. Down on the Adobe Walls crashed an avalanche of Indian horsemen. Before the warriors passed the wagon, behind which lay the five men with their long rifles, the medicine man and the negro began to lag behind to save their valuable skins. Finally in the midst of the chargers, the doughty pair came in sure range—then five rifles spat in unison. The medicine man threw up his arms, spun around and fell from his horse. The negro bugler hit the ground dead a second later.

The defenders now knew that their work was practically done. The Indians, with their leader dead, would hardly attack again. Then it was up to the five volunteers concealed behind the wagon to save their own scalps, for they would get no aid from within the Walls. The maddened Indians who had passed the wagon, and had recoiled before the bullets from the fort, were now attracted by the fire on their flank, and, swinging around, surrounded the wagon and group of five men, who made a desperate dash for the stockade gate, running through a confused tangle of horses, painted faces and feathered heads, with the roar and flash of rifles all about them. The two Shadley brothers were killed instantly. Dixon, a giant, gathered the two brothers under each arm and staggered into the stockade with their limp bodies, thus saving them from mutilation at the hands of the Indians. Tyler, running alongside Clinton, cried out that he was shot. Clinton slung the wounded man over his shoulder, and also reached the inside of the stockade unhurt. Tyler died a few minutes later. Only two of the five brave volunteers came back alive.

The Indians now withdrew behind the hills and held a council of war. They palavered a long time, but made no further attack on Adobe Walls. The battle and long siege was over and Sun Boy, the hereditary chief of the Comanches, whose star had been somewhat dimmed by the medicine man, was a wise Indian in his own way, and knew a losing game when he saw it. He and his counsellors made new medicine and decided that the Anadarko reservation, with government beef, was a far better place than the prairie where rifles of white men sprayed a leaden death. When the sun arose next morning the defenders of Adobe Walls beheld a welcome sight.. The Indians were "snaking " their dead warriors one at a time over the hills, always a preliminary movement to a disastrous retreat.

‹ Back