By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

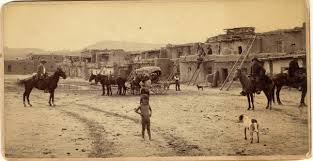

AN INDIAN RAID IN MEXICO

George W. Baylor

From Hunter's Frontier Times Magazine, September, 1948

In a quiet little Mexican town in the state of Coahuila, Mexico, long, long ago, was enacted one of the thrilling events now among the things of the past. The little pueblo of San Juan de Endes was located in a pretty valley about thirty miles southwest of Eagle Pass, a town where now the Mexican International railroad crosses the Rio Grande, or, as it is known in Mexico, Rio Bravo del Norte. The country is quiet enough now, but in 1850, the Comanche and Lipan Indians living in Texas, considered the Mexicans as legitimate prey, and each light moon witnessed foray by these savages.

The population of San Juan de Endes in 1850 was about 1500 souls, and the people lived by stock raising on a limited scale and farming. The Rio Fernando afforded water enough to irrigate between two and three hundred acres of very rich soil, which raised all the vegetables, fruits and grain needed by the inhabitants, and a good surplus over of frijoles (beans) that were as current as coon and bear skins were in Kentucky in early days.

The gamada (herd) of horses, cattle, burros and goats were each day sent out under little children to watch them, and the Mexican shepherd dogs, a fine breed of animals probably brought over from old Spain, always accompanied the little herders, and chased the sulking coyotes (prairie wolves) that lingered around the outskirts of the pueblo to get a breakfast by stealing chickens, pigs or anything they could kill and eat, and if no coyotes were found, then the dogs chased jack rabbits or cotton tails to the great delight of the children. who could take long sticks and twist the cotton tail out of the holes in the rocks or trees. It must not be supposed that no pains were taken to guard the lives of the little herders, for each morning, as a usual thing, a few armed men rode out to look for Indian sign (cortar la tierra), and if strange horse tracks or moccasins were seen the alarm was given, and the church bells rang out, giving notice to the men working in the fields, who, although armed, made for the adobe houses and walls of the pueblo, where the Indians were afraid to venture, and as soon as it could be ascertained the number of Indians, a sally would be made by the brave rancheros who, accustomed to these raids, made it quite hot for the Indians; and it was a race usually for the Rio Grande, the Indians making Devil's river (Rio Diablo) the point of escape, and usually having their villages fifty or sixty miles up that stream from the Mexican border. The Mexicans seldom followed them beyond the Rio Grande for fear of running into an ambuscade near these villages.

It happened on a bright June morning that a little boy of 9,years and his little sister of 6 were sent out with the herd and their mother had given them their dinner in a basket of frijoles, tortillas and tamales (their corn cakes and meat and pepper rolled in corn meal and wrapped in corn shucks). A few dried pasas de noas (raisins) made them very happy. Mounted on their little burros, (donkeys) the boy with his bow and arrow and the girl with the basket of dinner and a Mexican gourd of water, drove the stock galloping here and there with shouts and laughter as they saw the dogs nip the heels of the stock that refused to keep in the herd and then dropped on the ground when the donkey, horses or cattle kicked up high over their heads, but by the time their feet touched the ground, Shep was ready to nip their heels again and the only show for the stock was to run into the herd.

The children had reached the cienaga, a low, wet piece of land near the pueblo, and the stock had fed their fill on the rich green grass in the cienaga, and sought the shelter of shade under the trees. The children had eaten their dinner and fed the dogs, the latter after chasing coyotes, jackrabbits, couejos (cottontails), were tired and lying down, working their feet chasing an imaginary coyote in their dreams, giving a low growl occasionally. Nothing could. have been more quiet than the scene, and no thought of danger or Indians disturbed the children, but suddenly the dogs sprang up as if by one impulse and ran barking with bristles up. The boy grabbed his bow and they both ran into a little cave in the rocks, thinking it must be a lion (mountain lion), but the clatter of horses' feet and horrid yells told them their dreaded foe, the Indians, were coming. As quail do when scared, the children tried to to hide and escape to a thicket, but the sharp eyes of the Indians had marked them down and soon two warriors with hideous painted faces had grabbed them by their arms and swung them up before them, while some thirteen of their braves were rounding up the herd, and by waving their old blankets and buffalo robes and rattling their shields and yelling like demons they so terrified the herd that they were madly rushing away, the Indians chasing behind, shooting blunt arrows or prodding them with their lances.

The unusual dust and noise did rot long escape the vigilant eyes of the Mexicans, and soon the church hells were clanging, women screaming. dogs barking, men cursing and halloing to one another, and the men working in the fields came tearing in, driving their oxen, that seemed as much excited as their owners.

Soon a few men mounted on their best horses rode to the cienaga and saw the herd was gone, the dogs that fiercely defended their charges killed or full of arrows, and nothing could be seen of the children, nor could they find their bodies, so the supposition naturally was they had been carried off by the Indians. By the time the scouts made their report a party of twenty-one men had gotten ready to follow the Indians. The usual guard had made the circuit of the town in the morning and saw no signs but the wily Indians had evidently calculated the guard would only go to a certain distance from the pueblo, and they kept concealed at a safe distance, and allowed them to return before making a dash.

It so happened that a young American was in the town. He had been in Mexico during the war, being with the Tennessee troops, being quite young and a relative of General Persefor F. Smith. He had been around the general headquarters until the close of the war, and then enegaged in buying beans and corn for the troops at San Antonio and Fort Inge. His name, Tom Collins, became well known in after years on the Rio Grande, as he owned a mill in Carrizal, Mexico, and had a store in San Elizario, El Paso county, Texas. Tom had a good Mississippi rifle and a Colt's army revolver and hurting knife, and added a good deal to the effectiveness of the company. most of them being poorly armed.

The mother of the children was almost heartbroken, as she had little reason to suppose she would ever see her little ones again in this world, and filled the air with heP lamentations, in which her friends joined. Pobrecitos—probecitos ninon (poor little children) was the burden of their cry. Among the men who were going were the father and young brother about 18 years of age. They told the sad mother they would bring back the children or die in the attempt.

The company found the trail of the Indians and learned from it that there were fifteen Lipans in the raiding party. The old guide, who knew all the country and different tribes, settled the point by the arrows found. Tribes having different ways of marking their arrows, and even each warrior had his private mark. The direction of the trail, which was followed easily as they had taken quite a bunch of cattle and seventeen head of horses, and even after dark the moon shone brightly and the trail was plain. The old guide, having satisfied himself where the Indians would cross the Rio Grande, told them they had better leave the trail: first, because the Indians would leave out spies on the trail to see if they were followed; and second, because he could take them a nearer way.

They pushed on at brisk walk and jog trot, and the next morning by 3 o'clock came to the mouth of Rio Diablo. having rode seventy miles, nothing for the hardy rancheros and their tough mustang ponies.

The Mexicans struck the trail where the Indians had crossed the Rio Grande and camped under some large, beautiful shade trees on the north bank of the Rio Diablo. Here the Indians had evidently discovered they were followed, as their fires were still burning and they left some of the meat they were cooking on stakes before the fire. The weary men dismounted, and after eating concluded to stop and thus give the Indians the idea they had given up the chase, for they knew they would leave spies behind them, and in case they were hotly pursued would kill the children.

They unsaddled their horses and put out sentinels, taking every precaution to prevent a surprise and having their horses stampeded. Having cooked dinner and eaten, they saddled up at 12 o'clock and were again in the saddle and following the trail, which led up the north bank of Devil's river, and about six miles of travel brought them to the old pack trail between San Antonio and El Paso, where it crosses Devil's river at Cuevo Pinto (Painted Cave.) Here the Indians had struck across the big bend made by Devil's River, and which was forty miles before they would make the next camp where they could get water.

The Mexicans followed on until they got to Dead Man's pass, which is fifteen miles south of where old Camp Hudson stands. Here they halted just before sunset and got their supper and gave their tired horses time to rest and fill up on the rich, nutritious mesquite grass.

After dark they mounted and again took the trail, hoping to overtake the Indians before they reached the next crossing on Devil's river, and locate their camp either by the fires or their horses, for the Indians would by this time feel quite easy, and when they gave up all idea of being followed they are as careless as any people in the world, though they beat an old turkey gobbler keeping watch as long as they believe there is any danger of being followed.

Spies were sent ahead to keep a sharp lookout for the Indians, and sure enough they came back meeting us and said they had seen the Indian's horses and smoke from their camp fires. The spies had left the road before they got to the second crossing of the river, and there, near some grand old trees on the banks of a lake formed by the river the Indians were camped. The United States government afterward established Camp Hudson there.

The Mexicans got as near as it was safe to ride for fear of giving notice of their approach, for the horses are likely to whinney if they get the smell of stock they have been used to. Just before daybreak they dismounted 300 yards from the Indians, and leaving four men to guard their stock, they began to strip for the fight, taking off their shirts and their big old hats, which would give them away even in the dark, and piling them on the ground. They were then ready, and in Indian file followed one another noiselessly toward their sleeping foes, getting between the Indians and their horses. They crawled up close to the camp, forming a circle and getting the Indians between them and the lake. They quietly waited for it to get light enough to see the sights of their guns. Just as day began to break, an owl hooted, and this started all the old wild turkey gobblers within a mile to gobbling. The tired, drowsy Indians yawned lazily, and began to get up and stir their fires. A low signal was followed by a blaze of fire and the roar of guns, as the Mexicans charged with yells at the startled Indians, and so completely were they surprised that they never fired a shot, but left two quivers of arrows in camp with all their saddles, bridles and blankets, and what was best of all, the two little children, safe and unhurt. The Indians broke for the lake and some jumped in and swam across, but Tom Collins and his old brass mounted revolver sent one to the bottom. Some of the Indians ran along the banks, going upstream. and their trail showed plenty of blood.

The children being worn out had slept like rocks, and after the volley of guns sprang up and dived into a little thicket, but as soon as they heard the voice of their father, "Nina de mi Corazon," they knew they were safe and flew to the arms of father and brother. They all shed tears and Tom told me he got a little moist about his eyes.

The men soon were in their saddles and hastily rounded up the horses and found they had thirty head. One or two no doubt had stampeded when the attack on the camp was made. They all felt that it was not safe place for them, for the main Indian village might have been no great distance, and from the speed exhibited by the Lipans on leaving camp they had put little doubt the news would soon be at headquarters.

The children said the warriors had already settled among themselves which ones were to have them and were to adopt them into the tribe and put strings of beads around their necks. This was a common custom among the Indians. The men they nearly always killed, but women and children were taken alive and adopted into the tribe, and the children rarely ever attempted to escape, but the men and women would, so they preferred to kill them to keep from having to watch them all the time and run the risk of losing their best horses, for the best horse was always known in an Indian camp. and once mounted on him and a night start ahead of their pursuers, made an escape a pretty sure thing.

The company were four days getting back to San Juan, a courier having gone ahead to carry the joyful tidings to the mother of the recaptured children and the recapture, not only of their own horses, but the scoop made of the Lipan's horses, so the entire population turned out to welcome the returning heroes, for at that time the Mexicans were poorly armed to get the best of the Indians. Therefore, there was ringing of the church bells, joyous peals of victory. The victors came into the pueblo with the band playing, guns firing, banners streaming, and every evidence of unbounded joy.

The little boy and girl were hugged and kissed, and as much objects of interest as though they had never been seen before. A grand baile was in order, not before all had entered the sacred portals of the church and returned thanks for the victory, the safe return of the children, and the brave men who had punished the bold Lipans.

At the baile Don Thomas was the hero and the favorite of the dark-eyed senoritas, and had not only a corner in the hearts of the grateful Mexicans, but also in frijoles that well repaid him.

20,000+ more pages of Texas history, written by those who lived it! Searchable flash drive or DVD here

‹ Back

Comments