By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

BLOODY ATROCITIES IN JACK, YOUNG, PARKER AND PALO PINTO COUNTIES

W. K. Baylor, San Antonio, Texas

From Hunter’s Frontier Times Magazine, August, 1926

My inheritance and personal experience have bred in me a keen interest in Texas history, and particularly that part of it that is concerned with frontier events. When I use the word history, I do not mean romance. In order to make myself perfectly clear concerning romance, just turn to page 25, in the January 1925, number of Frontier Times, second column, and you will see what I call romance. Wolves do not go in gangs in Texas and never did. They do not howl when on a trail, and never did in Texas. I do not think it has ever yet been discovered that they have sufficient intelligence to know when a person or animal is weary, and follow such, expecting to be filled with their flesh. I have seen them (one) following a wounded deer. There is a reason for that. Wolves invariably flee when they see anyone. When hungry they will come into a camp and carry off anything they can eat, but attack you, never. Any old frontiersman will vouch for the truth of what I have just said above.

The massacre of the Mason and Cameron families in Jack county was another bloody page in our frontier history.

The list of murders in Jack county of families and individuals in the years 1857-59, is a large one. It is doubtful if there is any territory anywhere in Texas of equal size to that within the boundaries of Jack, Young, Parker and Palo Pinto counties, where the people suffered as much at the hands of the Indians as have those who, at an early day, peopled those counties. From 1856 up to and including 1864, Indian raids were frequent and the murders most revolting. And if ever men were heroes and deserved the gratitude of their countrymen, assuredly the few who fought so nobly on that frontier defending little children, feeble old men and women, who were murdered and mangled in the indiscriminate slaughter which considered neither sex nor helplessness, should not be forgotten. Our admiration for them should increase with the passing years. The utterly heroic attitude with which those people suffered and endured hardships and all manner of cruelties from savages ought to bind the hearts of all good people to them with unbreakable bonds of admiration and affection.

The Mason and Cameron families settled in Jack county in 1858. They built their cabins about a half mile apart. Ordinarily, when people first came into that country, knowing of the danger from Indians, they were very cautious and never left home without being well armed. but as time went on and no sign of Indians was seen in the particular neighborhood, the settlers would become careless and go to their work a long way from the cabin or visit in the neighborhood totally unarmed. And frequently their guns would be out of repair and their feeling of security so great that they would not take the time to repair them. I think a feeling of perfect security held sway when the above two families were attacked. Neither family ever fired a shot so far as we know. Yet, they were where they were liable to be killed any moment and had no arms. As above stated the two families settled in Jack county in 1858. Where they settled was about fourteen miles north from Jacksboro. They were completely isolated. Their nearest neighbor wag B. L. Ham, who lived some ten miles south of them, in the direction of Jacksboro. To add to the danger of these settlers the lower Indian reservation was only about. 35 miles distant, and on that reservation were some of the lordliest scoundrels who ever escaped the gallows. Complaints multiplied through 1857 and 1858, of thefts and murders traced to the lower reservation. The wild tribes on the plains, chiefly Comanches, depredated almost without hindrance, and the malefactors of the reservations laid all the blame on them. The citizens on the other hand thought most of the trouble came from the reservations. The wild tribes on one side and the reservations on the other made the location of the Masons and Camerons a very dangerous one as the after events clearly proved.

The father of Mrs. Mason, Jacob Lynn, lived on Keechi Creek, some 12 or 14 miles distant.

In the spring of 1859, while Mr. Cameron and a son, who was about sixteen years old, were at work on the farm some distance from the house, the first intimation they had of danger was when they were attacked. The circumstantial evidence—their tracks indicated that when they were attacked they ran towards the house and were killed when they had gone but a short distance. The Indians then went on to the house and killed Mrs. Cameron in the cow pen. Whether she was milking the cows, or went among them with her baby to hide I do not know, there being no evidential evidence in the case. What I do know is that she was foully murdered and the baby left to crawl around in its mother's blood in the pen of cows. No doubt, the reason some cow did not gore the baby was due to the fact that it was too small to leave its mother and the cows would not approach the mother.

ENJOYING THIS STORY?

On this same day and no doubt near the same time, Mason, his wife and baby were killed and the elder two were scalped and their bodies otherwise mutilated. These were killed some little distance from their cabin. Why they were away from the only protection they had I do not know. It is probable they were at work as the Camerons were and the Indians were upon them before they knew it. After killing the Masons the house was searched by a redheaded man, so the Mason children are reported to have said, and he and his associates took whatever valuable thing there was in it. It was currently reported that Mr. Mason had money, but none was found after the murderers left. A trunk was broken open by the red headed man and if Mr. Mason had any money "that Red Headed Man" got it, as he had done before and as he did afterward. Two little boys of the Mason family were not killed. Why they were not killed I do not know any more than I know why they failed to kill the Cameron baby and the other Cameron children. I have a very strong suspicion, however, that they did not kill them for the reason that they thought the crime would not be discovered because of the distance to any other settlers and the children would die of starvation before they could be rescued and they preferred to kill them in that way.

When the murderers left they took with them two of the Cameron children, a little boy about eight years old and a little girl of six. These two little ones were carried many miles from home and released in a howling wilderness, not however, until the little boy's throat had been cut and left for dead. Both these children were rescued and I saw the boy. Wit Cameron, after he was a grown man and the sear on his throat told the story of his captivity.

The murder of the two families was not discovered until the forenoon of the third day alter it was committed. On this day Jacob Lynn, the father of Mrs. Mason, went to visit his daughter and found the conditions I have just described. How unutterable must have been the anguish of the father at beholding the indescribable picture of horrors. Two little children left at the Mason's who were almost starved to death. The baby of Mrs. Cameron was found in the cowpen beside the decomposing body of its mother nearer dead than alive after its long fast, and six dead and mutilated bodies. Before arriving at the scene, Mr. Lynn heard an unusual lowing of cattle. Upon drawing nearer he saw a terrible commotion with the lowing. This at once aroused Mr. Lynn's suspicion. The cattle had been in the pen since the evening before the murders and were nearly dead for want of food and water. Upon discovering the black crime Mr. Lynn, by some means not known to me, and perhaps not known to anyone else, now made known what had happened and the dead were given such burial as could be given under the circumstances and the little children were tenderly cared for by sympathizing friends and relatives.

It was just such savage cruelties as I have described above—and there were many such—that caused the frontiersmen to rise up in righteous indignation in the spring of 1859 and run the Indians out of Texas. See October Frontier Times, 1924, page 4, where it will be noted that when the Texans arrived at the lower reservation they found the Indians nearby comfortably nestled in the folds of the American flag, which was a disgrace to it, and every State in the Union. There was always food, shelter and protection for the Indian but none such for the frontiersman and his wife and little ones, except such as he could work out for himself, hampered on all sides. And whatever he may have hoped for in the way of protection, certain it is that none ever came until the frontier was drenched with the blood of its men, women and children. The dragging years passed and he saw them empty of protection always. It is possible, that we are too near the marvelous deeds of our frontier people to properly appreciate them. My hope and trust is, that sometime in the near future better justice will be done them than has ever yet been done them.

"Go with me into a frontier home— Browning's for instance. In that humble cabin sits an old man over the dying embers. Beside him sits a grayhaired. brokenhearted mother, their heads bowed low by a crushing sorrow. The hearthstone is bathed with tears. Their lone cabin is in deep mourning. Their boy, the hope and joy of their last years, sleeps beneath the sod. There is an expression of infinite sadness that fills their unsmiling eves. Suddenly they raise their bowed heads to the flag of their country; and it mocks their agony in its violated promises of protection. No marble slab tells the sad story, but look into their sad hearts and you will find inscribed there: `My poor boy! My little children! My husband! This is the work of the savage and his scalping knife. This is no idle tale to lead off the imagination. It is truth."

On the 18th day of May, 1871, the Comanches and Kiowas, an hundred strong from Fort Sill, invaded Jack county and attacked a wagon train hauling provisions for the troops at Fort Griffin. There were ten teamsters; seven were killed, one of whom was tied to a wagon wheel and slowly burned to death. The Indians, plundered and burned the train, and, driving off some forty of the mules, returned to Fort Sill and boasted of the exploit. Three of the teamsters escaped, one of them wounded and bleeding, to Jacksboro, twelve miles distant, where there was a regiment of cavalry. The officer cursed the poor fellow and swore he did not believe a word of his report. There was a general order that Indians committing depredations should not be pursued. That's very dreary reading in view of all the facts.

These Indians were murdering and plundering in a country they never claimed nor occupied. They clearly understood, however, that they had authority from the United States authorities to rob and murder in Texas. At the time of the murder of the teamsters they had on their reservation more than fifteen hundred head of horses, all notoriously stolen from the settlers in Texas and they had been bringing in their scalps and prisoners for years without any disapprobation being expressed or implied.

In 1869 a band of Indians, seven in number from Fort Sill came into Bosque County on a stealing and murdering expedition and were all killed by the citizens in a fight. Each one of them had a pass from the agent at Fort Sill, who was highly indignant because the Indians were killed.

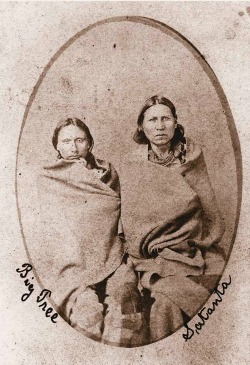

When the Indian chiefs Satanta, Satank and Big Tree were arrested for killing the teamsters near Jacksboro, they regarded the arrest as an act of treason on the part of the white man. I think the agent must have regarded the arrest pretty much as the Indians did. He may not have given those Indians passes, and yet he may have done so, knowing exactly where they were going and for what. The owner of the train destroyed by the Indians was Captain Henry Warren who was a New Yorker and had served in the Union army. That fact it seems made a difference. Some Indians were arrested.

In January, 1871, Brit Johnson, with two other negroes, was hauling corn and cornmeal from Parker county to the soldiers at Fort Griffin. One night they camped on Salt Creek in Young county. Early next morning they were attacked by a large body of Indians and all three of them murdered in cold blood. Nothing was ever done about this killing as usual, but Brit Johnson and his associates were entitled to as much consideration as Captain Henry Warren and his teamsters.

In 1871 the Indians killed Charles E. Rivers, an account of which has already been published in Frontier Times. At the time of the killing of Brit Johnson Charley Rivers was ranching at the old Peeveler ranch about three miles east of where the Indians had made the attack on the negroes. Mr. Rivers heard the shooting and started to where it was, but upon nearing the place there was so much shooting—several hundred shots— he knew he could render no service, so he returned to the ranch and thereby, no doubt, saved his scalp until June following, when he was killed.

The murders were occurring pretty regularly in the little area I outlined in the beginning. From January to June eleven persons were murdered.

In April, 1871, the Comanches scalped Lin Cranfill near Weatherford, and on the 16th of April surrounded a party of citizens near the line of Palo Pinto and Young Counties and killed and wounded eight out of twelve of the number. In May they committed other murders in the area, and there was none to molest them nor make them afraid.

There was a garrison of soldiers at Fort Sill, a cavalry regiment at Jacksboro, soldiers plenty at Fort Griffin, but they had as well not been there at all, for all the protection they gave the frontier. Their mission seemed to be to protect the Indian rather than the citizen. If they did not have orders not to pursue the Indian, they acted as though they had just such orders.

How about 20,000+ pages (352 issues) of Texas history like the one you just read?

Texas history, written by those who lived it! Searchable flash drive or DVD here

‹ Back

Comments