By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

CAPTIVITY OF THE SIMPSON CHILDREN

From J. Marvin Hunter's Frontier Times Magazine, Vol 18 No. 05 - February 1941

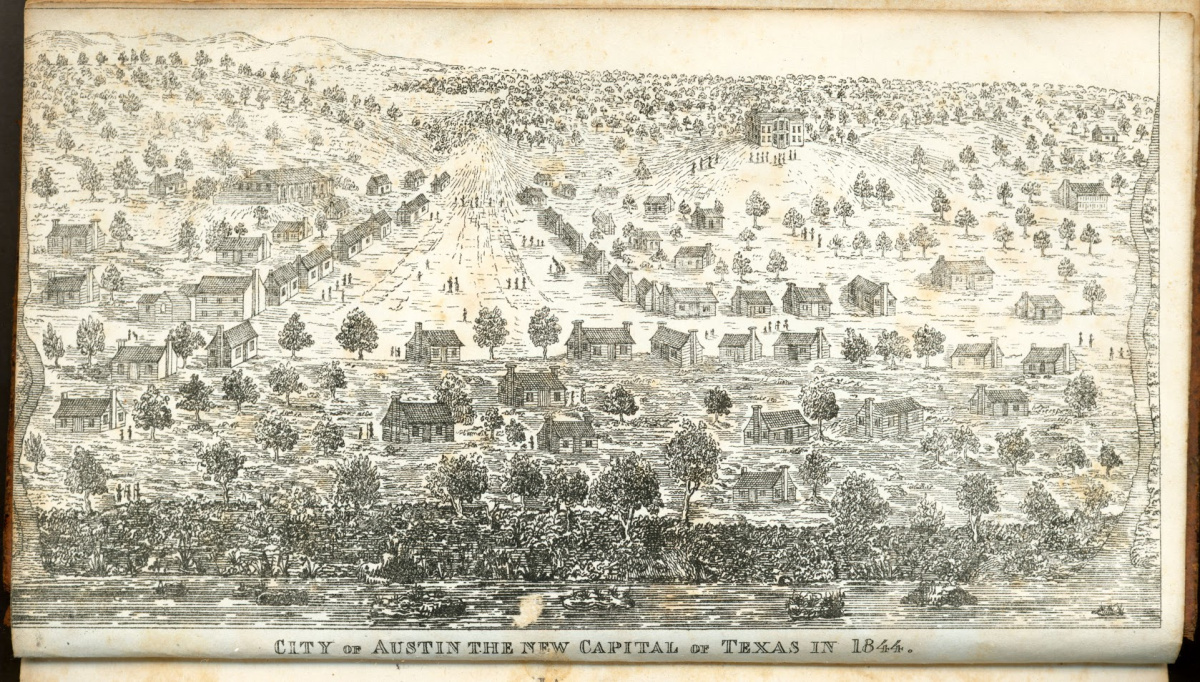

Among the residents of Austin in the days of its partial abandonment, from the spring of 1842 to the final act of annexation in the winter of 1845-6, was an estimable widow named Simpson. During that period Austin was but an outpost, without troops and very exposed to inroads from the Indians.

Mrs. Simpson had a daughter named Emma, fourteen years of age, and a son named Thomas, aged twelve. On a summer afternoon in 1844, her two children went out a short distance to drive home the cows. Soon their mother heard them scream at the ravine, not over 400 yards west of the center of the town. In the language of Col. John S. Ford, a part of whose narrative I adopt: ''She required no explanation of the cause; she knew at once the Indians had captured her darlings. Sorrowing, and almost heartbroken, she rushed to the more thickly settled part of the town to implore citizens to turn out and endeavor to recapture her children. A party of men were soon in the saddle, and on the trail.

They discovered the savages were on foot -- about four in number -- and were moving in the timber, parallel to the river, and up it. They found on the trail shreds of the girl's dress, yet it was difficult to follow the footsteps of the fleeing red men. From a hill they discovered the Indians just before they entered the ravine south of Mount Bonnell. The whites moved at a run, yet they failed to overtake the barbarians. A piece of an undergarment was certain evidence that the captors had passed over Mount Barker. The rocky surface of the ground precluded the possibility of fast trailing, and almost the possibility of trailing at all. Every conceivable effort was made to track the Indians, and it proved unavailing. They were loath to return to Austin to inform the grief-stricken mother her loved ones were indeed the prisoners of savages, and would be subject to all the brutal cruelties and outrages of a captivity a thousand times more terrible than the pangs of death. The scene which ensued, when the dread news reached Mrs. Simpson's ears, can not be painted with pen or pencil. The wail of agony and despair rent the air, and tears of sympathy were wrung from frontiersmen who never coiled when danger came in its most fearful form. The pursuing party was small. All the names have not been ascertained. Judge Joe Lee, Columbus Browning and Thomas Wooldridge, were among them.

Pursuit under the then condition of the almost defenseless people of Austin was impossible. No further tidings of the lost children were had for a year or more. About that time, Thomas Simpson was ransomed by a trader at Taos, New Mexico. He was finally returned to his mother, and then the fate of Emma became manifest. Thomas said his sister fought the Indians all the time. They carried her by force, dragged her frequently, tore her clothing and handled her roughly. Thomas was led by two Indians. He offered no resistance, knowing he would be killed if he did.

The Indians then divided for a short time, the sister in the charge of one and the brother of the other couple. When they reunited on Shoal creek, about six miles from Austin, Thomas saw his sister's scalp dangling from one's belt. No one will ever know the details of the bloody deed. Indeed, a knowledge of Indian customs justifies the belief that the sacrifice of an innocent life involved incidents of a more revolting character than mere murder. In the course of time the bones of the unfortunate girl were found near the place where Mr. George W. Davis erected his residence, and to that extent corroborated the account of Thomas Simpson. It is no difficult matter to conceive what were the impressions produced upon parents then living in Austin by this event. It is easy to imagine how vivid the conviction must have been that their sons and daughters might become the victims of similar misfortunes, suffering and outrages.

In the language of Col. Ford: ''Let the reader extend the idea, and include the whole frontier of Texas in the scope, extending as it did, from Red river to the Rio Grande, in a sinuous line upon the outer tiers of settlements, and including a large extent of the Gulf coast. Let him remember that the country was then so sparsely populated it was quite all frontier, and open to the incursions of the merciless tribes who made war upon women and children, and flourished the tomahawk and the scalping knife in the bedrooms and the boudoirs as well as in the forests and upon the bosoms of the prairies. When he shall have done this he can form an approximate conception of the privations and perils endured by the pioneers who reclaimed Texas from the dominion of the Indian and made it the abode of civilized men.

Click the image below:

‹ Back

Comments