By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

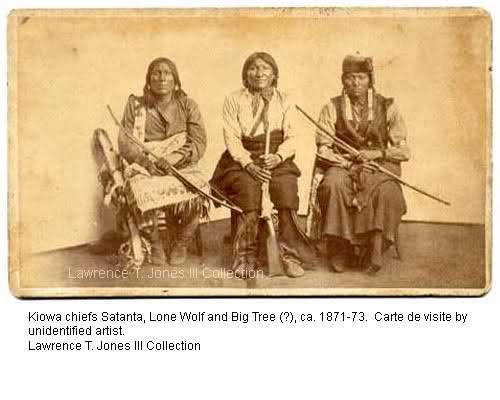

CHIEF SATANTA'S ELOQUENT SPEECH / MASSACRE OF HENRY WARREN'S TRAIN

From J. Marvin Hunter’s Frontier Times Magazine, May, 1938

At a peace council held in October, 1867, on the Arkansas river, in the present state of Oklahoma, between United States peace commissioners and the principal chiefs of four Indian tribes, Satanta, principal chief of the Kiowas, said:

"It has made me glad to meet you, the commissioners of the Great Father. You, no doubt, are tired of much talk of our people. Many of them have put themselves forward and filled you with their sayings. I have kept hack and said nothing—not that I did not consider myself the principal chief of the Kiowa nation—but others, younger, desired to talk, and I left it to them. Before leaving, however—as I now intend to go—I come to say that the Kiowas and Comanche have made with you a peace, and they intend to stick to it. If it brings prosperity to us, of course we will like it better. If it brings poverty and adversity, we will not abandon it, because it is our contract, and it will stand.

"We hope now that a better time has come. If all would talk and then do as they talk, the sun of peace would forever shine. We have warred against the white man, but never because it gave us pleasure. Before the day of apprehension came, no white man came to our village and went away hungry. It gave us more joy to share with him than it gave him to partake of our hospitality. In the far distant past there was no suspicion among us. The world seemed large enough for both the red man and the white man. But its broad plains seem now to have contracted, and the white man grows jealous of his red brother. He once came to trade; he now comes to fight. He once came as a citizen; he now comes as a soldier. He once put his trust in our friendship, and wanted no shield but our fidelity. He once gave us arms and powder, and bade us to hunt the game. He once made a home and cultivated the soil; but he now builds forts and plants big guns upon their walls. We then loved him for his confidence; he now drives us to be his enemies. He now covers his face with a cloud of jealous anger, and tells us to be gone—like the offended master speaks to his dog. We thank the Great Spirit that all these wrongs are now to cease, and the old times of peace and friendship are come again.

"You come as friends. You have patiently heard our complaints. To you these complaints have seemed trifling. To us they are everything. You have not tried, as many do, to get our lands for nothing. You have not tried to make new bargains merely to get the advantage. You have not asked to make our annuities less, but unasked you have made them larger. You have not withdrawn a single gift, and voluntarily you have provided new guarantees for our advantage and comfort. When we see these things we say, 'These are men of the past.' We at once gave you our hearts. You have them. You know what is best for us all. Teach us now the road to travel, and we will not depart from it forever. For your sakes the green grass shall not be stained with the blood of the whites. Your people shall again be our people, and peace shall be our mutual heritage. If wrong comes we shall look to you to right them. We know you will not forsake us. Tell your people to be as you have been.

"I am now old and will soon join my fathers; but those who come after me will remember this day. The time has now come when I must go. Goodbye. You may not see me again, but remember Satanta, the white man's friend."

It is hard to understand how any human being, after uttering the lofty sentiments expressed in the eloquent speech quoted above, could go out from that peace council and continue the heartless butcheries he committed. The speech is a model of simplicity, eloquent in language, and ennobling in thought. It was after this speech that Satanta, Satauk and Big Tree captured Henry Warren's wagon train near Jacksboro, in Jack county, Texas, tied the captured teamsters to the wagon wheels and burned the entire train, including the helpless men, which resulted in their trial at Jacksboro. Texas, the first instance where an Indian was tried in the civil courts of Texas for murder. In this trial Satanta was convicted and sentenced to be hanged, but the sentence of death was later commuted to life imprisonment, by Governor E. J. Davis of Texas, and he was later paroled and allowed to go back to his people. Even after this he continued his butcheries, murdered little children, and carried away their mothers and sisters into a captivity far worse than death. It would seem that their pitiful cries and shrieks would be sufficient to damn his soul forever by an avenging God.

In November, 1874. Satanta was recaptured, and placed in the penitentiary at Huntsville, where he finally ended his life by jumping or throwing himself from an upper window of the prison.

_____________________________________

Love Texas history?

Join our Facebook closed group here

_____________________________________

MASSACRE OF HENRY WARREN'S TRAIN

From J. Marvin Hunter’s Frontier Times Magazine, April, 1947

The day following General Sherman's ride over the government road leading from Fort Griffin to Jacksboro, one of the most horrible Indian massacres in the annals of Texas history took place near the Young county line. And it was this foul deed which caused the General to positively make up his mind in favor of a different Indian policy by his government. In the commanding officer's quarters of the old territory post it was definitely agreed that the Kiowa chiefs were to be held to "strict accountability" for this Young county massacre.

The Kiowas were on a government reservation at that time and were actually living out of white men's hands, yet they depredated upon them mercilessly. In 1869 a treaty of peace had been made between this tribe and the Washington government, but throughout the East the policy of "benevolent assimilation" was so popular that it was being followed by most of the Indian agents. At the very moment Sherman was in Fort Richardson, the Indians swooped down upon a wagon train owned by Henry Warren, which carried freight between Fort Richardson and Fort Griffin, and murdered seven of the guards. The savages chained one of the guards to a wagon wheel and literally roasted him to death, laughing in his face as he begged for mercy. There were 150 Kiowas in this attack on the party of twelve guards and teamsters. They were led by Satanta, Big Tree and Satank, the former being a most treacherous Indian chief, who was described as "a beggar in the pale face's camp, a demon on his trail." This was the straw that broke the camel's back and caused the reversal of a policy that was depopulating a big part of Texas.

When the teamsters and guards saw the savages rushing down upon them, they quickly corralled their wagons and defended themselves as best they could, but the odds were against them. Only five men of the wagon train party escaped and one of these was badly crippled. The five hid in dense brush until the foe departed. Satanta boasted of this outrage to the Indian agent and seemed to think that he had committed a deed against the Tehannas (Texans) that would be pleasing to the Great White Father in Washington.

When General Sherman took Satanta to task, however, he declared that Kicking Bird, Lone Wolf and certain of his young and foolish warrior chiefs were responsible for the Warren wagon train massacre. He proved himself to be a miserable craven and tried hard to beg off, but the General told him that he was responsible for cowardly murder and that he would have to face his accusers in the courts of Texas.

He was then heavily chained, along with Big Tree and Satank and sent to Jacksboro, Texas, for trial. While the prisoners were returning from the trial, Satank released himself, grabbed a gun and undertook to shoot one of the guards, but a well directed volley suddenly ended his career. The other two prisoners were tried in district court a short time later. Sam Lanham, later Governor of Texas, was the prosecuting attorney, and both chiefs received the death sentence. Later, however, the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, by E. J. Davis, and the Indian chiefs were placed behind the bars of the State penitentiary.

Following General Sherman's visit to Texas and his inspection of various frontier forts in the Southwest, the government inaugurated a vigorous campaign in Texas against the redskins. General Mackenzie. who was in command at Fort Richardson, fought a decisive battle with the Kiowa and Comanche Indians in Palo Duro Canyon, September 25, 1874, defeating them so completely that their power for offense was thereafter broken. During the progress of this battle Mackenzie killed about 1500 head of the Indians' horses so as to keep the remnants of the tribes from making further raids on white settlements.

General Grierson, in command at Fort Sill, was removed to Fort Davis, and helped to clean up the section infested with hostile Indians west and northwest of Fort Worth. Later General Grierson was sent to Fort McKavett, at the head of the San Saba river, and in conjunction with General Mackenzie's soldiers, fought an engagement with a band of Indian raiders near the town of Menardville. The raiders were killed, most of them, and the surviving ones fled over the adjacent hills, chanting a weird and plaintive tune as they departed for the last time from this, their favorite haunt, of Southwest Texas.

20,000+ more pages of Texas history, written by those who lived it! Searchable flash drive or DVD here

$129.95 $89.95 $49.95 (For a limited time!)

‹ Back

Comments