By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

GILLESPIE COUNTY TRAGEDIES

This series of Frontier Stories was written several years ago by John Warren Hunter, now deceased. One article of the series will appear each month in Frontier Times.

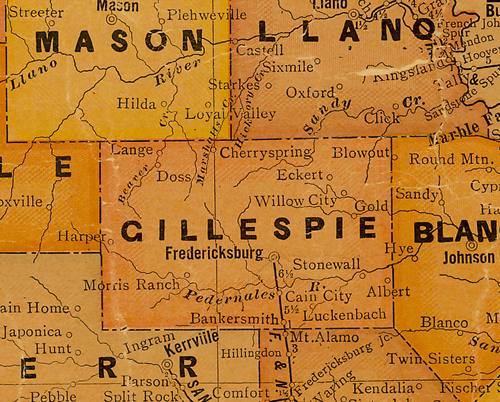

Early in 1855, Matthew Taylor and Joe McDonald, each having large families moved from Illinois and settled on Spring creek, fifteen miles west of Fredericksburg in Gillespie county. At that period Fredericksburg was the chief seat of the Prince Solms Colony of Germans and was a mere village of pole cabins, and the settlement formed by McDonald and Taylor was on the extreme border. The government maintained a small garrison of regulars at Fort Martin Scott, two miles below Fredericksburg, also at Ft. Mason and later in the year, (1855) Fort McKavett was established. The Messrs. McDonald and Taylor engaged in stock raising and farming, the latter only to a limited extent where the waters of Spring creek could be utilized for irrigation. These men were devoutly religious and when their little log cabins had been completed, and ready for occupancy, a family altar was erected, the Bible was installed as their man of counsel and their children taught to worship God and obey His divine precepts.

Nature was bountiful to these couriers of a new order of things. Game was plentiful. Wild bees abounded in tree and cave, and life would have been one long joyous round of rural joys but for the continued menace of the savage in whose path little settlement was made.

Mr. Taylor informed the writer that hunting grounds in those days embraced the Upper Llanos, the Conchos and the Guadalupe regions and that during the Buffalo season he and his sons and the McDonald boys paid their annual visit to the Conchos, established their camp near the spring at the confluence of the two main streams and where San Angelo now stands. Here they would remain until the buffalo had left or had been driven out and then they would return to their homes laden with dried meats sufficient for the year's supply.

Mr. Taylor also informed me that he and his brother-in-law, Joe McDonald, were the first to raise a crop of corn in Kimble county. The spot chosen for the agricultural experiment was in the forks of the Llano, in the river bottom where the two Llanos came together just below where Junction City now stands. With a rude "bull-tongue" plow they prepared the ground - some two or three acres - planted the corn and returned to their homes on Spring creek, thirty miles away. Later they came back and plowed and hoed out their crop.

When the corn reached the roasting ear stage, bears came in for their share of the harvest but sufficient was left to reward the pioneers for all the labor expended.

Shortly after the advent of the Taylor's and McDonald's. the Nixon and Joy families moved out from Arkansas, the Nixons settling on Squaw creek and the Joys on Beaver creek. The points of the two settlements were respectively ten and sixteen miles from the Taylor settlement on Spring creek, but in those days of ceaseless peril, little count was taken of distance and a man living twenty miles away was a door neighbor and the sense of a common danger, resolved into a kinship of the close ties of which the present generation can scarcely comprehend.

Just before the outbreak of the Civil War, Monroe McDonald married Miss Beckie Taylor, daughter of Matthew Taylor. About the same time Lafe McDonald married Miss Alwilda Joy, a sister to Tobe Joy, who later made a brilliant record as an Indian fighter.

To the old frontiersmen it was well known that an Indian never forgets or overlooks a locality or settlement where one of his tribesmen has been slain. Vengeance sooner or later was sure to be wreaked upon the dwellers of that particular locality.

The settlers in Gillespie were not seriously molested by the Indians until the beginning of the Civil War when U. S. troops were withdrawn from the frontier. Up to that period, they were in a measure friendly, visited the settlements occasionally, traded with the people, and sometimes departed with horses not paid for.

The first of a long series of trouble with these pioneers began in 1862. An Indian approached Monroe McDonald's cabin and begged for food. Monroe supplied his wants and took him to his father's, Joe McDonald, where he was kept under guard a few days and then delivered to the sheriff of Gillespie county, who placed him in jail. What became of the Indian is not positively known. He disappeared and the report went abroad that they meted out a cruel, swift vengeance as the sequel will amply show.

Early in February. 1863, Captain John Banta, with ten others, among whom were the McDonald boys, were scouting along Johnson's Fork of the Llano. The day was cold and a light mist was falling. They came upon an Indian trail leading in the direction of the Spring creek settlement and by that almost intuitive knowledge peculiar to the frontiersmen of those days, they soon found that there were eleven Indians in the bunch, and that they were all on foot. They took up the trail and cautiously followed it until they reached the crest of a divide overlooking the head draw of the Pedernales river. where they suddenly came upon the Indians, who, suspecting no danger, had halted on the bench of a hill and were engaged in mending their moccasins, which, owing to the wet grass and long travel, were nearly worn out. The boys charged upon the Indians, who in turn fled and attempted to reach a mot of live oaks in the valley below. The Indians became scattered and a running fight ensued. Each Texan selected his Indian and when crowded the savage would turn upon his pursuer and attempt to raise his bow and arrow. But the misting rain had dampened their bow strings (made of sinew) and this rendered the weapons useless. The Texans were almost at an equal disadvantage, although armed with Colt's revolvers. The ammunition furnished by the State was very inferior, more especially the percussion caps. These were not waterproof and had become damp. Nor were they of the gauge to fit the tubes of the Colt's pistol when placed on the tubes, the first fire would jar the remaining five loose and they would fall oft. But the battle grew apace. The Indians finally rallied around their chief whose yells of defiance would have stricken terror to weaker souls. The mounted Texans made repeated charges until six of the braves had fallen, among whom was their chief. The remaining five escaped in the brush and were pursued for some distance, but without avail.

During the last charge a shot front Captain Banta's pistol had broken the old chief's back. While pursuing the fugitives, the wounded chief had dragged himself to a nearby live oak and when the pursuers returned they found him reclining against the root of that tree. As they came up he began to chant his death song, the weirdness and novelty of which caused them to pause and hear him to a finish. The chief held in his grasp a long knife and at the conclusion of his song and when Mr. Banta stepped forward to give the parting shot, with an effort, calling forth all of his remaining strength, the Indian plunged the knife into his own heart and fell back a corpse.

Six scalps, six bows, six quivers of arrows and a few worthless articles of Indian apparel were the fruits of victory. But there were six Indians less to steal and plunder, and the Texans came home without a scratch.

Some time before this, about the year 1860, if I have been correctly informed, the Taylor and McDonald ranch was established on the Pedernales, where Harper now stands, and some 8 to 10 miles from Spring creek. Lafe McDonald, it seems, after his marriage, lived with or near his father-in-law, Mr. Joy on Threadgill several miles distant from the Taylor ranch.

During those heroic days the clothing worn by these pioneers was either "home spun" or buckskin and sometimes both, and the cotton cards, spinning wheel, winding blades and warping bars were indispensable industrial implements in every frontier home.

_____________________________________

_____________________________________

A few months after Captain Banta's tight just above the Taylor ranch, and where six of the enemy were killed, Mrs. Lafe McDonald and her mother, Mrs. Joy, left the Joy ranch in a buggy and started to the Taylor ranch with a lot of thread they had span and which was being taken to Mrs. Taylor to be woven into cloth. Some miles out, they were surrounded by a band of Indians and killed. To show the settlers that this raid was strictly one of revenge, these Indians did not appropriate the horse driven by the murdered ladies nor did they take any article from the buggy. The first intelligence the family had of the awful tragedy was when a couple of hours after the two ladies left the ranch, the horse came back still harnessed to the buggy and stopped at the gate. When the family went out to investigate, they found both of the women in the buggy dead. Mrs. McDonald's head had been severed and it was found under the buggy seat. Mrs. Joy's throat was cut from ear to ear. John Joy, Sr. the husband and father, swore eternal vengeance against the Comanche when he viewed the remains of his wife and daughter. He was in fairly good circumstances. He owned a large stock of cattle, horses and hogs besides an ample supply of specie. He called his sons around him at the conclusion of the funeral and announced to them his resolution to devote the remainder of his days to the task of destroying Indians. To these sons he gave charge and control of all his stock and ranch interests, reserving for himself shelter and food on occasions when he chanced to return from his long and weary search for the enemy; and means sufficient to supply him with the latest improved arms and ammunition.

From that date only one thought, one intense, burning desire - that of revenge - swayed the life of Mr. Joy. He seemed to avoid the company of men, always going alone, sometimes going on foot, but more often mounted. It is related of him that for several years he rode a stocky Spanish horse, fleet of foot and of a hardihood that seemed proof against all manner of fatigue and hardship. This horse was never known to leave him, and while he would not allow a stranger to approach, yet he was ever ready to come to his master’s call. From instinct or other cause, this horse had an abhorrence for Indians and while encamped in forest or plain, if an Indian came near at any hour of the night his presence was made known by the stomping and snorting of the intelligent animal. The old pioneer was an apt pupil in all that pertained to Indian woodcraft, and soon became as adept to the extent that the fresh turned stone, a broken twig or bruised blade of grass attracted his notice and ofttimes indicated the late presence of the enemy. His activity and endurance was almost superhuman. Today, on one of the Twin Mountains on the Concho scanning the adjacent plains and the distant horizon, watching for a smoke from signal fires; tomorrow, from some high peak overlooking the valley of San Saba, the next day steadily examining the watering places along the upper Llano's - in vale, hill, mountain and cedarbrake - a phantom of grim tragedy, a silent, ghostly Nemesis that never slept - always on the alert - moved by a single impulse, that of an unquenchable, insatiable consuming desire - revenge. Such was Veteran Joy.

It seemed as if this brave old pioneer had become possessed with the power of ubiquity since it is related of him that he was always found of the trail of every band of Indians that raided the region from the Guadalupe to the Colorado, and when an Indian ventured within the confines of all that vast region, quite often he found, when too late that an avenging Nemesis was on his trail, and whose steady aim never faltered and whose trusty rifle never spoke in vain. Returning home on one occasion from a long scout in the Llano region, and when within a few miles of his ranch, his quick eye discovered Indian sign, and upon closer scrutiny he found the trail of three Indians that had passed along afoot, in the direction of the Taylor ranch. Taking this trail, he silently, swiftly followed. It led him to the west of the Taylor ranch and across the divide. The second day at nightfall, with the tread of a lynx he came upon them in their rude bivouac in a cedar brake on the banks of a little stream. They had shot a cow and were regaling themselves with roast beef, when a rifle shot pierced the heart of one of their faithful number and the deadly Colt's did the rest. All three were killed.

This old pioneer died at an advanced age. He lived to see the Comanche forever banished from the Texas border, but lamented the government's course in placing the tribe on a reservation, and feeding them at public expense. He thought they all ought to be killed and regretted that he could not live longer and kill a few more of the numerous devils.

On the Taylor ranch lived Matthew Taylor and his wife, Hannah, a number of their children, and Eli McDonald, his wife and six children. On one occasion, Mr. Taylor and his son with one or two neighbors, went away on a cow round-up, leaving Eli McDonald to look after the ranch and protect the families. On the morning after the departure of Mr. Taylor and only a few hours after his leaving, a large body of Indians appeared. Not suspecting danger so near at hand, Miss McDonald, a beautiful girl just blooming into womanhood, had gone to the spring nearby to bring the milk from the spring house for the noon meal. As she left the spring she was riddled with arrows, and with frightful yells the Indians swarmed into the yard and around the home. Mr. McDonald seized his Winchester and rushed into the yard to repel the enemy. The Indians made sign for peace and motioned for him to put away his gun; that they were "muy amigos." Finding such fearful odds against him, in a moment of weakness yielded and set down his gun against the side of the house. Seeing this movement, several Indians came forward with extended hand as if for a friendly handshake. McDonald offered his hand which was seized and while being held was stabbed to death.

With the fall of Eli McDonald the butchery stopped. Mrs. Taylor and Mrs. Eli McDonald and her children were witnesses to the tragedy and were powerless to offer any resistance. The Indians looted the place taking everything that struck their fancy. They were noisy and in high glee and while sacking the house Mrs. Taylor stealthily passed out into the cow pen where a large number of her home cattle were basking in the shade of the trees, and among these friendly kine she concealed herself until the Indians had departed. Mrs. McDonald and children were carried into captivity but at the end of three years were released by government agents and restored to relatives in Gillespie.

This Indian raid was made only a few months alter Captain Banta's fight with the Indians, only a few miles above the Taylor ranch.

A few years after Mrs. McDonald’s release from captivity, she was married to Peter Hazelwood. During the last raid ever made by the Indians in Gillespie County, Mr. Hazelwood was killed in a fight with them on the waters of Spring creek. This was in 1872. Seven or eight years later Mrs. Hazlewood married again and at last accounts was living at lngram in Kerr county.

When the Indians, laden with household plunder which they securely packed on horses, had taken their departure, Mrs. Hannah Taylor quit the ranch and in her fright and bewilderment started, she scarcely knew where. The following day the people at Doss ranch, twenty-five miles from the Taylor ranch, were startled by the appearance of Mrs. Taylor. Her frail shoes had been worn out over the stony ground and her feet were bleeding from innumerable lacerations and abrasions. Her hands, arms and face were covered with blood from having come in contact with catclaw and other thorn-bearing brush, while only fragments of her raiment yet clung to her sorely wounded body. Her reason for the time being, had been overthrown, the ordeal had been greater than she could bear and only incoherency, the babblings as of a little child, and paroxysms of maniacal laughter, came in reply to inquiries from those ranch people, who soon came to realize the crushing weight of her misfortunes, Couriers were sent in all directions to the different settlements for aid in punishing the Indians. Mrs. Taylor received every care and attention that generous souls could suggest, and after long months of suffering, recovery came and she lived to a ripe, old age. Matthew Taylor, her husband, was a Methodist preacher, and shortly after her thrilling adventure with the savages, Mrs. Taylor became impressed with the idea that she had a divine call to the ministry, and in obedience to the call she eventually became a preacher after having professed sanctification and joining the holiness people. The writer knew her quite well and heard her preach on many occasions. She was very fervent at camp meetings and often raised a shout of praise and thanksgiving to the Lord for her deliverance. A common expression of hers when shouting was: "Bless the Lord, the Indians got me, but I got away agin!”

Don't miss the current special: download 352 complete issues for only $89.95. You'll have all the stories you could ever read! Click here!

‹ Back

Comments