By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

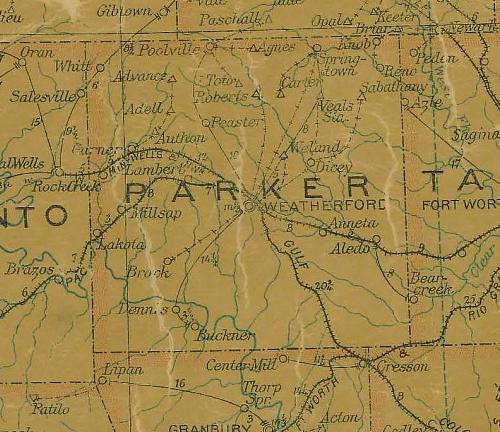

INDIAN ATROCITIES IN PARKER COUNTY

From Hunter’s Frontier times Magazine, August, 1944

Hon. G. A. Holland

In July, 1862, Hiram Wilson and his brother-in-law, Mr. Fulton, were preparing to make sorghum. They sent William Wilson, 12, and his cousin, Diana Akers, 10, an orphan girl, to drive up steers that were to pull the sweep to grind the cane. The Indians, seven in number, captured the children about 10 a. m., and forced each of them to ride behind an Indian to Mount Nebo, about three miles away, which is nine miles south of Weatherford. They spent the day there, Diana crying all the time. The Indians kept a lookout most all day from the top of a tree, where they could get a good view. Late in the afternoon the captors got much excited; a caravan of covered wagons came in sight of the Weatherford road with many loose horses, just the kind they were looking for. They went into camp not far away. When night came on, two of the Indians guarded the children, while the other five went after the campers' horses, which they secretly drove away.

By mimicking owls as a signal, the Indians got together with the prisoners and horses. They drove near the home of the captives, where the children heard the familiar bark of the family dog and the crowing of the rooster. Riding behind their captors, the party crossed the Brazos, the waters glistening in the moonbeams, but its beauties meant no more to them than did the lonesome howl of the wolf, or the hideous hoot of the owl. They were rushed on, in constant fear of death, little Diana crying all the while. They traveled all the dreary night, going through parts of Parker and Hood far into Erath county. When daylight came they had gone so far they felt secure, and stopped for rest and sleep. They rolled the boy in a blanket to keep him from trying to run away and laid him on the ground. Diana lay down by his side, all bruised and sore from the long ride, and they slept a little. Diana's eyes were red and swollen from crying and loss of sleep. The children expected all the time to be killed.

In breaking camp they seized the children, tied both onto an old roan mare, turned them loose and drove them with the herd. During the day they killed calves they found on the range and ate the meat raw. The children, though starving, could not eat the raw flesh. The Indians loitered along Sunday creek until night. They killed a cow and with a knife and flint kindled a fire, scorched some of the meat for the children, a little of which they ate without salt. This was the third day out. When night came they made a long drive for a pass in the Palo Pinto mountains, near where Ranger note stands. The children were still riding the old roan mare, but were not tied on. They began to have less fear of being killed and talked as they went along, trying to lay plans to escape.

When the party got nearer the top of the mountain, the Indians seemed to get suspicious and waited for a while. They howled like a wolf, gobbled like a turkey and hooted like an owl, but got only the echoes from the valley. They moved on very slowly and cautiously, two Indians in front, next the two children on the old roan, then the herd of horses and the other five Indians in the rear.

Just as they reached the top of the mountain, a volley of rifle shots rang out in the clear, still, moonlight air. With the first shot the horses were killed from under the two Indians in front, and the old roan from under the children. The Indians disappeared, but the shooting continued. The persons shooting thought the children were Indians and kept shooting at them, killing horses all around them, until they screamed and held up their hands, making them understand that they were captive children. The attacking party was composed of about thirty rangers and citizens who were waylaying the pass for another bunch of Indians known to be in the country. The children were taken to Stephenville, where Diana was found to be so bruised and sore from the long ride that she could not travel horseback. Other means of conveyance was provided and they were sent home, with enough captive experience to last the remainder of their days.

_____________________________________

12 FREE HARD COPY EDITIONS OF "FRONTIER TIMES MAGAZINE"

We are reducing our inventory of hard copies, so we'll throw in 12 COPIES FREE!

See below article

_________________________________

In April, 1865 James McKinney and family, his wife, a girl 6, a boy 3, and a baby in its mother's arms, living in Jack county, had been to Springtown on a visit and to do some shopping. While there he traded his six-shooter for merchandise. They traveled in an ox-wagon as was the custom at that time. They stopped at noon at the P. M. Jenkins home, later the John Frazier home. When leaving there they asked for the Jacksboro road.

William Shadle, father of the lamented Sam Shadle, deceased, and our esteemed townsman, Virgil Shadle, gave the following account of one of the most brutal Indian depredations in the county, a copy of which was found among Sam Shadle's papers after his death:

Mr. Shadle and a man by the name of Jenkins were hunting cattle in the north part of the county near Agnes. While riding along a sandy trail Mr. Shadle saw small tracks in the sand. Jenkins contended they were coon tracks. They followed only a little way when to their surprise a weak, small voice called from the brush, "Papa, papa." On looking they found a little boy three years old, entirely nude! When the child saw neither of the men was his father, he tried to run away. Mr. Shadle caught him and found his little body full of brims and scratches and his side pierced with a lance. The Indians had stripped him, pierced his side and left him for dead. He lived through the night and escaped wolves and other wild animals, but could not tell who he was nor why there, except to say, "Booger man did it."

Mr. Shadle wrapped the child in his saddle blanket, took him to the home of William Kincannon some distance away, but could not get him identified. They then went to Mr. Jenkins' home, where they learned from Mrs. Jenkins that a family passed there the day before inquiring the way to Jacksboro. Mrs. Jenkins, with the help of Mrs. William Shadle, now of Poolville, picked the briars and thorns out of the child's body, dressed his wounds, and put clothes on him.

Shadle and Jenkins, with others, returned, and about a mile from where the child had wandered or been carried, found the wagon hung against a tree, with an arrow in one of the oxen; they soon found Mrs. McKinney had been killed and scalped. The father, who evidently had tried to protect the baby, was also murdered and scalped. The baby had been taken by the heels and hurled against a tree and a wagon hub, which was shown by unmistakable evidence. The little girl, 6, was carried away. On following the trail they found fragments of her clothing. It was supposed she fought and cried until the Indians killed her. The mutilated body was found. The remains were loaded in a wagon and taken to Goshen and buried in one grave. The little boy, Joe McKinney, grew to manhood near Springtown, then lived for many years at Jacksboro.

In the year 1867, Isaac Briscoe lived one-half mile north of Agnes, in Parker county, with his wife and two daughters, 14 and 16, and two smaller children. They were honest, hardworking, Christian people, living happily and contented, as did the settlers of that day. Mr. Briscoe had a turning lathe with which he made furniture for the settlers. He was operating it under a large grapevine shade when a band of between 75 and 100 indians dashed up to his unprotected home. They killed and scalped Mr. and Mrs. Briscoe, and with a broadaxe chopped up their bodies in the presence of the children, then took all the horses and household goods they could find. They took the two young ladies and the two smaller children captives and carried them away. No trace of them was ever obtained. It was as though the earth had swallowed them up, and in the absence of any report of what happened, and what the captives were forced to endure, we feel that it would have been much better for them if they had been murdered on the spot. The young ladies were just reaching womanhood— lighthearted and free, with the prospects of a useful and happy life before them. A sad reflection to us—father and mother slain, little brother and sister's fate unknown, perhaps killed in their presence; that which awaited them could not be foretold. The worst we can imagine might have been consolation when compared to what did happen.

Mr. and Mrs. Briscoe were buried in the same grave at old Goshen, where in their unmarked resting place they await the final judgment day. It is hoped that on that resurrection morn the missing children will be united with father and mother. There went a family of six, with not one left to tell the story.

Onward went the tyrants, with booty and prisoners, passing the Culwells, Mayos, Montgomerys and others and gathering up horses and robbing home.

Hez Culwell, long-time Poolville resident, and Tom Mayo went to Mr. Allen's to give the alarm. The Indians got there at the same time, shot at them, killing Mayo's horse from under him. The boys ran through the house. Hez carried one of Mrs. Allen's children and she the other. They went out the back way, down a creek bank out of view, waded the creek bed through holes of water and carried the children to safety. When the Indians found the Allen home vacated they took charge and appropriated everything of use to be found. Mrs. Allen afterwards made an inventory of their loss, which she reported as being: Five feather beds and five straw beds, 40 quilts and blankets, 400 pounds of flour in sacks, all their clothing except what they had on; all dishes that were not taken were broken; a new piece of homespun cloth just finished and still in the loom, which represented many months of work, and other small articles not mentioned. We give this that the reader may have a better understanding of what occurred when a home was robbed by Indians.

20,000+ more pages of Texas history, written by those who lived it! Searchable flash drive or DVD here

$129.95 $89.95. $69.95

included in your order (for a limited time)

12 FREE HARD COPY MAGAZINES!

‹ Back

Comments