By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

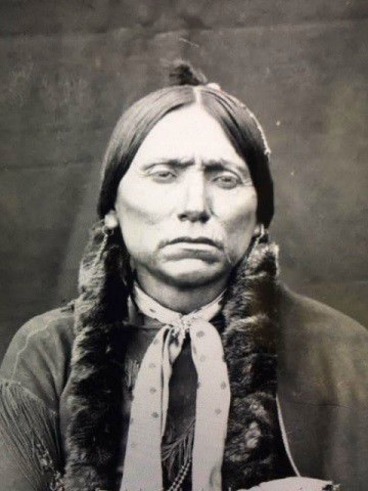

QUANAH PARKER, CHIEF OF THE COMANCHES

From J. Marvin Hunter’s Frontier Times Magazine, June, 1947

Quanah Parker, who became chief of a branch of the Comanche tribe, was one of the most remarkable Indians that ever lived. For a time he made war on the whites, because he was an Indian, and he felt that the white man was his enemy. I have known several men who knew Quanah well, and they all praised him as a most just and high-minded man. One man who admired him most was Herman Lehmann, who was captured by the Indians when he was a small boy, and grew up among the savages, he himself becoming a wild Indian, but was later restored to his people and became re-civilized. Herman Lehmann was with the tribe when Quanah and his people went on the reservation to take up the white man's ways, and he stated to me that Quanah had often warned his people that the doom of the Indian was at hand; that the best thing they could do was to yield to the superior race and become peaceable children of the great White Father at Washington for the buffalo were gone, and their wild free life was over.

All through the life of Quanah Parker is found evidence of a dual existence led by the man through whose veins the blood of a proud white family and the wild blood of the Indian were intermingled. This strange blending of the blood of two naturally hostile races produced a character the like of which the world has never seen. He was, as will be revealed later on in this article, both stern and relentless while, at other times, he was gentle as a woman.

The story of Quanah Parker starts with his grandfather. The mother of the famous half-blood was a white woman of a splendid ancestry. This was a decided exception to the rule. It was not unusual in the far West for an adventurous white man to wed an Indian girl and become absorbed into the tribe of which she was a member, but white girls, no matter how plebian of blood, never married Indians. In the fact that his mother had broken this precedent lies the unusual background of Quanah Parker.

It was in the period between the years 1835 and 1840 when the Parkers, an honorable and esteemed family, came pioneering into Texas, that this story had its beginning. In the group were the father and mother, their sons and daughters, their wives and husbands, and numerous grandchildren. Texas had just wrested her hard-won freedom from the iron hand of Mexico, and the venture of the Parkers was a most hazardous one. Hostile Indians and marauding Mexicans roamed at will over the sparsely settled prairies, plundering, and the few hardy spirits who ventured into this new land lived in constant danger.

It was but a short time after the Parkers had erected their rude huts near what is now Groesbeck, Texas, that disaster came riding down upon them with the swiftness of a cyclone. Equally swift was the destruction wrought by the blood-seeking Comanches who attacked them. In the brief but futile struggle of the defenders, many of the white women and children were slain. Others were driven on foot some distance from their homes. Others were taken captive. Among these last were a small boy and girl, Cynthia Ann and John, aged 9 and 6, respectively.

No possibility of their rescue existed. The settlers were few and dared not go on such an expedition for fear of what might happen to their own families. In those perilous days the pioneers could only accept things as they were, smother their heartbreaks and pray that the worst might be spared them.

Before any word of the kidnapped children came back to the little settlement, years had passed. Then, during a brief respite from hostilities between the Indians and the settlers, a venturesome visit into a Comanche camp was made by some white hunters, friends of the Parkers. They saw Cynthia Ann, now a grown woman.

The hunters called on the chief and sought his permission to have a word with the girl. After much cajoling and persuasion, his consent to the interview was obtained on condition that he be present at the meeting.

The interview was a strange one. Through it all Cynthia Ann maintained a stolid silence, her face inscrutable as that of the bronzed Indians with whom she lived. The only emotion betrayed by her was in the quivering of her chin.

The interview ended and the white hunters mounted their horses and rode away. As they rode strange, unanswerable questions were asked among themselves. What was the cause of Cynthia Ann's silence? Had she grown so shy as to be unable to tell what she knew of the past? Had the stolidness of her Indian sisters impressed upon her an unbreakable habit of silence? Perhaps the horror of seeing her parents massacred long ago had unbalanced her mentally, or else fear of the old chief, who stood at her side, had locked her tongue. No one ever knew the cause of her reticence.

So it was that Cynthia Ann, who was born for better things, grew to lovely maidenhood amid the rough environment of the Comanches. Under the custom of the tribe she married Peta Nocona, who was known as the most courageous of all the Indian braves, and in time became the mother of Quanah Parker.

So rapacious did the Comanches finally become that the State of Texas sent forth punitive expeditions to combat them. It was in one of these forays, under command of L. S. Ross, that Peta Nocona was slain and Cynthia Ann captured.

But she had seemingly forgotten the English language, so long had she dwelt with the Indians. Her once fair skin had been burned by the western suns until it was as black as that of the Indians. Her body was dirty and she was poorly, even scantily clad. Every feature of the fair little girl, who a quarter century before had seen her parents cruelly murdered, had vanished. A frightened silence was the only answer she gave her questioners. In the hope of awakening her long dormant memory, Captain Ross told her the story of her capture by the Indians.

When he concluded with the words, "And so Cynthia Ann was carried away," the awakening he had hoped for came. As her eyes sparkled and her face shone with delight, she pointed to herself, and said, "Me Cynthia Ann."

Word of the girl's discovery was sent to her uncle, Isaac Parker, who was now a prominent businessman and politician of Texas. He came for her and took her to Austin. There she was placed in the home of her brother, one of the little fellows who was driven by the Indians into the woods on that eventful day so many years before.

But the freedom of life with the Indians had wrought its spell. She could never reconcile herself to the quiet ways of civilization. A constant watch had to be maintained to keep her from answering the call of the wild and returning to the free life of the Indian camp. Life in the open was too inured in her veins and the habits of twenty-five years had woven so strong a chain about her that the weaker links of civilization were unable to hold her unfettered spirit. And so, ever mourning for the freedom of the plains, Cynthia Ann died a short time after her capture.

Now for Quanah Parker's own story.

The death of his father and the capture of his mother left the future chieftain a pauper at fourteen. He had nothing upon which to rely save his cheerful disposition, magnetic personality and hunting ability. Since he needed very little of life's necessities, these traits served him well.

With the Comanches was a comely maiden known as Weckeah. She and Quanah had been friends since childhood, though there had been no talk or thought of love between them. One day Weckeah came to Quanah and told him that her father, Yellow Bear, had been offered ten ponies by Taanaap for her hand in marriage. This news brought to Quanah the realization that his life-long friendship for the girl had ripened into love. But he labored under the handicap of possessing only one pony. To overcome this embarrassment, he used his powerful personality among friends, with the result that the other nine ponies were soon placed by friends at his disposal.

_____________________________________

_____________________________________

Then another obstacle arose. Eckitoacup, Taanaap 's father, and unsuccessful rival of Peta Nocona for the hand of the white girl, Cynthia Ann, made an alluring offer of twenty ponies for Weckeah. Even friendship has its limitations, and Yellow Bear, knowing this, accepted the twenty ponies immediately. The marriage feast was set for three days later.

But the childhood friends, now lovers, had other plans. That night, while Quanah waited near her tepee, Weckeah stole out to meet him. Twenty stalwart braves were there to protect the bride in case of attack. Eloping with the promised fiance of another warrior was unlawful and a tribal crime. In case of capture the punishment would be swift and sure death for both man and woman.

But the coup of Quanah and his bride was successfully executed and the band made good their escape. For ten hours they rode without stopping save to water the ponies. For two days this swift pace was maintained then they halted on the banks of the Concho river, in Southwest Texas, where they made permanent camp.

Quanah became more and more widely known as he grew older. The peculiar circumstances of his birth played a large part in his career, and the blood of his white ancestors endowed him with keen business sense and remarkable character. He began to realize that if the Indian was to survive, he must adopt the ways of the white man. Accordingly he changed his way of living. He abandoned his nomadic wanderings and horse thefts. By his example he became an excellent factor in teaching his people the ways of civilization.

His new program greatly stressed the advantages of education. He introduced the building of homes, started a definite plan of agriculture, and encouraged the practice of thrift. Laziness and dissipation met the frown of his disapproval.

Although he retained many of his beliefs in the ancient customs of his tribe, he adopted many of the white man's ways. He entered politics and became a power among the affairs of his people. He was named as judge of the Indian court and was chosen by the people to fill several county offices. He and Theodore Roosevelt were close friends, and if Quanah had not been a bigamist, Roosevelt would have given him a responsible Federal position.

Quanah increased the treasury funds of his tribe by leasing their pasture lands for $100,000 annually. He made frequent trips to Washington as a representative of the Comanches. At these times he clad himself in the garb of civilization, though on the reservation he was content with the blanket and mocassins of the Indian. On his trading expeditions into the nearby towns he presented a most resplendent figure, being over six feet in height. He would come to town wearing a tall silk hat, in addition to his blankets, in a fine carriage, which was drawn by a team of splendidly matched gray horses. One of his wives usually accompanied him, but never stopped at the hotel with him, preferring to camp out on a creek. Occasionally she would stay in the hotel kitchen and eat with the negro cook.

Toward the white man, Quanah maintained an attitude of great friendliness. Quite often he entertained his friends in his palatial home on Cache Creek, in the Wichita mountains of Oklahoma. There were fourteen rooms in this house. The fact that his many wives and children lived here in peace and comfort gives further proof of the greatness of this peculiar man, who had grown very rich through his vast herds of cattle and agricultural pursuits.

It was not by the usual method of teaching or preaching that Quanah Parker elevated the Comanches, but by his own example. He was not an educated man or a Christian, yet his desire for higher standards of living changed his status in life. Had he chosen fully the ways of his white friends, the Parkers would have accepted and educated him as the son of Cynthia Ann. But he preferred to be an Indian, and his decision undoubtedly lost to the country a great statesman and scholar.

With him service was a fetish. Instead of preaching it, he gave it. By the world he was called an Indian, yet from the white blood in his veins undoubtedly came his business sagacity. These characteristics caused him to stand out as a prominent figure in Texas and Oklahoma history.

He died in 1911, and is said to have been the first Comanche chief to die in a civilized house, in bed, as became a white man and a gentleman.

Can you think of a better stocking gift this Christmas? An entire TEXAS HISTORY LIBRARY written by those who lived it - over 20,000 pages worth! Click the links below to get yours.

20,000+ more pages of Texas history, written by those who lived it! Searchable flash drive or DVD here

$89.95

Option 2

Get 352 issues packed with stories like the one you just read

$69.95

‹ Back

Comments